Ivan Peries (31 July 1921 - 13 February 1988)

Chapter XIII

The Romantic Exile

Ivan Peries’ poetry

The problem with Ivan Peries was that he could not be dismissed with a convenient critical phrase or be put out of the way with an easy tag. He was mercurial, and so too did his work have that quality. Until the very last years of his life his paintings had the air of a whim or a fancy, allowing the subject and his reaction to it to suggest the style, yet always communicating a romantic and beguiling poetry. All sorts of things stimulated his imagination: colour sometimes as in the triptych of blazing landscapes with their golden reds and crimsons glowing in a fierce tropical sky: shapes, as in the portrait of the girl in her First Communion dress, an austere arrangement in greys and whites, as in the case of the portrait of Whistler’s mother: mystery, as in the deep forebodings of the sea and the rumblings of a monsoon equally full of awe, as in the painting known as The Return. There is stark realism in the anxiety with which the family awaits the return of the men gone out to sea. And what Ivan Peries had to an outstanding degree was the craftsmanship with which to achieve all this.

IVAN PERIES: Two figures in red. Part of a triptych. Oil on canvas (40cm x 60cm). Pam Fernando Collection. Colombo

He was profoundly interested in the right choice of materials and he very much enjoyed the technicalities of painting. Quite early in his career he was to acquire an appreciation of these matters. He first began drawing lessons under David Paynter in the early 1940s in Colombo, and at these classes he was to meet and develop a great friendship with Aubrey Collette. When Paynter left to go on to Almora in northern India to look after 115 orphaned children, Lionel Wendt recommended Harry Pieris as a teacher. Harry Pieris was himself a fastidious master of the craft and was to remain in Ivan Peries’ mind as the finest of all teachers. The association grew into a lifelong friendship; and Ivan Peries’ admiration for his guru would have seemed all the more astonishing if you did not have an appreciation of Harry Pieris’ own skills. Ivan Peries’ four years in London from 1946 at the St Johns Wood school of art on a Government scholarship did not influence his loyalties. He very much enjoyed the school, and it was here that he discovered the technique of tempera which he used very infrequently because it was so time-consuming. All this experience contributed hugely towards Ivan Peries becoming so much of a legend and a master of the craft in his own right.

Meanwhile, however, local critics remained wary of him. L. P. Goonetilleke was only able to say that Ivan Peries was “trying his hand out and his work in this exhibition (the inaugural ‘43 Group show), indicates his ability to evolve a personal idiom.” The following year, the same critic found him “still on the track with a Whistler mood.” The tentative nature of the critics’ comments was to be seen in such careful observations as: “bolder and surer in touch, has a number of interesting studies, the titles of which hardly matter”; … “now an old and tried hand is engagingly satisfying, and bolder and more frank in what he has to say.” In a way this was saying something of Ivan Peries’ personality. It was volatile: he could easily fly off into a routine of his own, for which he earned the sometimes affectionate nickname of Ivan the Terrible. He was most suspicious of critics and often described them as frustrated artists. Ivan Peries used to trail behind him a stout cane walking-stick which he held by a black, leather knob. It alarmed quite a few people but hurt no-one but himself. One afternoon, running down Dickman’s Road to avoid a shower of rain he tripped over it and came to us bruised all over and feeling very sorry for himself!

IVAN PERIES: Christ by the Sun. Centre panel of triptych. Oil on canvas (91cm x 60cm). Pam Fernando Collection, Colombo

Lester James Peries, who was living in London at the same time wrote to his parents about his brother’s work: “Martin Russell … will bear me out when I say that he (Ivan) has never painted such ambitious and colossal and magnificent pictures. They are assuming such vast proportions that I wouldn’t be in the least bit surprised to find ourselves squeezed out of the flat owing to considerations of space. One painting on which he is now working hard and which Martin has bought even in its present state of incompleteness is almost 10 ft by 7 ft.” Lester Peries said that his brother’s work, in Martin Russell’s opinion, “has now the indications of future greatness.”

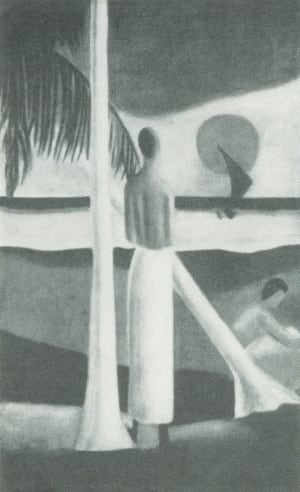

IVAN PERIES: The Return. Oil on canvas (56cm x 86cm). Anton Wickemasinghe Collection, Colombo

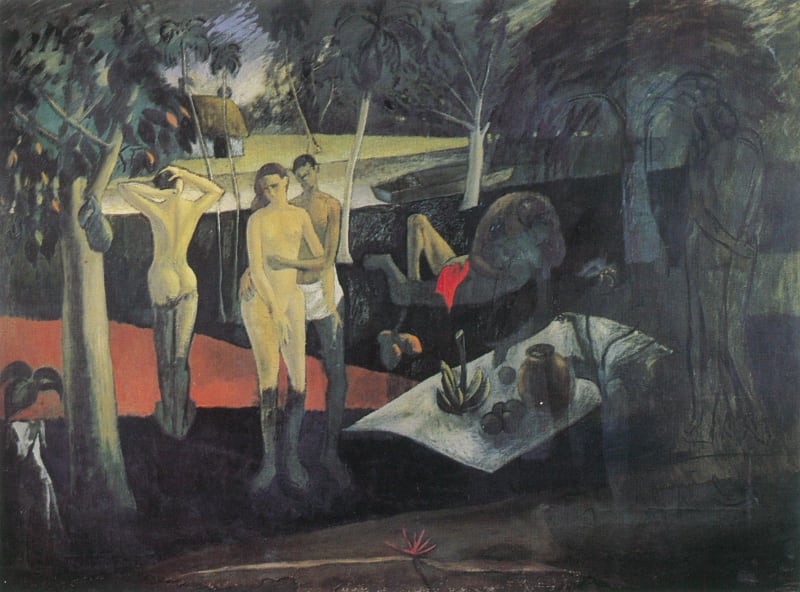

Aubrey Collette was to write: ‘There’s little doubt that there are very few in Ceylon who possess the gifts of Ivan Peries as a painter, and no one who has worked more consistently to develop them.” Upon viewing his work at the ‘43 Group exhibition at the Imperial Institute in London in 1952, the art critic Maurice Collis was to write: “After looking for a while at Ivan Peries’ large canvases of bathers I began to come under their grave charm and thought how surprised and delighted we should be if when travelling in Ceylon we found them decorating the interior of some big house in Colombo.” The Manchester Guardian critic found that Ivan Peries had “evolved a strongly personal style and has entirely digested and made his own the influences which shaped him. His palette is dark without being sombre and there is a serenity in the figures …” George Butcher writing in Arts Review (2 June 1961) of the exhibition at the Oueenswood Gallery said. “His pictures are very classically conceived; they invite the contemplation of calm moments: and they are the very opposite of all those pictures today that scream raucously in many voices …”

IVAN PERIES: Bathers. Oil on canvas (275cm x 204cm). Sapumal Foundation, Colombo

Senake Dias Bandaranayake has devoted a great deal of time to the study of Ivan Peries’ work. In 1969 he wrote: “In spite of having spent a major part of his life as a painter abroad, there is nothing in his work which is outside the Ceylonese experience, nothing which displays a distance in subject, style or attitude from Ceylonese life or Ceylonese modes of feeling … It is the work of a singular and original creative mind nurtured throughout two decades abroad by the lasting experience of a distant homeland.”

The highly textured, almost monochromatic compositions of his last years were a logical development of his tendency to simplify to the point of austerity – one might even suggest, like Beethoven’s String Quartets – depending on a distilled palette and consumed in a deep nostalgia. The austerity is monastic and surely was derived from Ivan Peries’ great affection for the work of Piero della Francesca and Fra Angelico. But there is also more than a mere vestige of the sensuous in the paintings, in the linear movement that inhabits the paintings which, as in El Greco, is yet innocent of all guile and artfulness. This is precisely what gives the paintings that feeling of the timeless dispassionately observed and expressed in sensual images which are entirely within our own experience. If the images have a touch of the melancholy, that is the poetry we are called upon to contemplate.

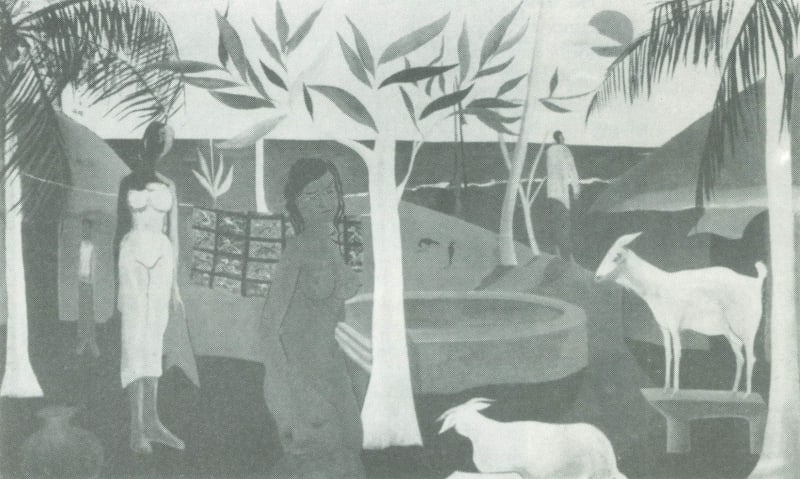

IVAN PERIES: The Well. Oil on canvas (250cm x 102cm)

He was, as he said, the prime mover in the formation of the ‘43 Group, and he was present at the preview of the first exhibition. He told with enormous glee of the discomfiture of Dr G. P. Malalasekera, then president of the Ceylon Society of Arts when confronted by a wildly gesticulating Justin Daraniyagala giving him a lecture on what was what in the art of painting. And of the robed Manjusri Thero shocking a polite society woman by drawing her attention to a sexual element which he insisted was implicit in all his paintings.

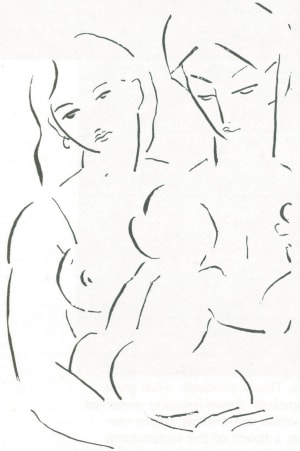

IVAN PERIES: Illustration for Rosalind Mendis’s Nandhimitta

Upon his return from London late in 1949, Ivan Peries arranged to give classes at Cora Abraham’s art school in Dickman’s Road, Havelock Town. This included formal life drawing and a great deal of discussion. He was totally absorbed in his Catholic traditions and took great pleasure in such institutions as the monastic life and other mediaeval practices. He liked the notion, for instance, of the , pupil being apprenticed to his teacher on a fulltime basis; and it was in this manner that I became associated with him between 1950 and 1951. It was to take me directly into the preparation of his first solo exhibition consisting of some 125 paintings, drawings, water colours and pastels, which took place at the new premises of the Photographic Society of Ceylon in Galle Road, Kollupitiya, in September 1951. This meant, of course, hanging the pictures and seeing the catalogue through the printers; ) and organising the great barrel of toddy which was served at the preview. It also involved rescuing old canvases which had been stored away in the attic of the Peries home in Dehiwela, restoring parts of a portrait that had been mutilated, repairing others, preparing new canvases for the “master” and helping with the framing. And in the style of the mediaeval painter’s apprentice, filling in spaces. Cleaning the palette and washing the brushes after a day’s work became part of the routine.

Ivan Peries returned to live in London in 1953 and worked at various jobs for which he had neither the will nor the inclination – as messenger, builder’s mate and hospital worker – to earn a living while he continued to paint. He did precisely that, and the evidence of this was several one-man exhibitions held in Europe and in Colombo, an exhibition with the work of Harry Pieris, and another with that of Richard Gabriel. The exhibitions also included a collection of eighty paintings and drawings in October 1965 at St Catherine’s College, Oxford; and fifty-three works at the Commonwealth Institute Gallery in 1966. His paintings form part of several important private and national collections in many parts of the world including the Petit Palais in Paris; the Martin Russell collection, London; the Sapumal Foundation, Colombo; the Anton Wickremasinghe collection, Colombo; Pembroke College, Oxford; Leicester Education Authority, Leicester and the War Memorial Museum, London. And they were seen not only at the first ‘43 Group exhibition at the Imperial Institute in London, but at the Petit Palais (1953); AIA Gallery, London (1954); Hefler Gallery, Cambridge (1954); the XXVIII Venice Biennale (1956); the XXIX Venice Biennale (1958); South London Art Gallery (1960); Bear Lane Gallery, Oxford (1961 and 1963), the Beaux Arts Gallery, London, and others.

IVAN PERIES: Man and Boy. Triptych. right panel. Oil on canvas (40cm x 60cm). Pam Fernando Collection, Colombo

On Ivan Peries’ death on 13 February 1988, Ian Goonetileke contributed an eulogy which appeared in the Lanka Guardian of I March and which he ended as follows:

“His paintings at their best and most sustained level incorporate a specific oriental flavour in the traditional modes of linear composition, adroit placement, and an intensity of feeling. We are never not moved or touched by their affinity to a spiritual rhythm or a mystic sense. Both grief and ecstasy are transmuted into pastoral images of a sensitive, yet restrained, tenderness. To have known him and his work was a rare and enriching experience.”