Chapter I

The Gathering of the Fold

The past and the present

Let me start with a platitude: Sri Lanka after the end of the Kandyan kingdom early in the 19th century, lay in a void. A kind of malaise hung over the country to be punctuated only by two fierce expressions of discontent, the first in 1848 – the so-called Kandyan Rebellion – and in 1915. But meanwhile the temples had been suppressed and so the only painting that was undertaken at that time came to an end, not to be revived again until late in that century when Queen Victoria repealed the law. Her portrait and that of Prince Albert preside over the entrances of several temples on the South coast in somewhat naive acknowledgement of the queen’s initiative.

Having said that, we need to make two statements of principle: that art is didactic at its worst, decorative at its metaphysical best – an idea developed extensively by Lionel de Fonseka in On The Truth Of Decorative Art: a Dialogue between an Oriental and an Occidental (Greening. London 1912), and elaborated upon by Dr Ananda Coomaraswamy in innumerable essays on the subject. Apart from the murals painted on temple walls by village craftsmen who used their skills to explore details of the life of the Buddha or tp illustrate the Jataka stories or to provide devices traditionally required in exorcist rituals, no painting in the manner of Europe, or for that matter, in the exclusive and secular manner of the court painters of Rajput or Moghul India, appears to have been undertaken. The temple painting of Sri Lanka was demonstrative, that is, didactic; and decorative, that is, metaphysical. They have the essential characteristics of the masterpiece; high art in whatever language you wish to discuss them.

That this work was of great intrinsic merit was left to the industry of men like the sometime monk. L. T. P. Manjusri, to show; and the scholarship of Coomaraswamy, to argue. It is good to recall that Manjusri, with single-minded purpose and encouraged by people like Harry Pieris, scoured the countryside to copy and annotate the mural paintings he found, often in abandoned temples in remote jungles, and sometimes in not so far-away urban wildernesses.

Ananda Coomaraswamy was particularly concerned for the preservation of pristine Sri Lankan art. His Open Letter to the Kandyan Chiefs, sent to each individually and published in the Ceylon Observer of April 1905, drew attention to the danger of neglect faced by various buildings of the 17th and 18th centuries, vihares and devales among them, in the Kandyan district. He was quite optimistic that “the much older buildings of Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa are not at present in much danger of neglect or injudicious restoration.” He remarked: “In repainting vihares nowadays the chief errors lie in the bad colours; ill-judged attempts at the introduction of perspective; careless and ignorant, nay, often irreverent work, and the introduction of unsuitable objects. I say bad colours because the old way of making colours has been given up, and with it all restraint in the use of colour, so that where a few colours only were used (mainly red, yellow, black, white and greyish green), the painting now displays all the colours of the rainbow; and at the same time the beautifully conventionalised and restful traditional style is abandoned in favour of a weak and ineffective realism, so that the inside of a vihare whose walls were once covered with worthy and decorative paintings are now as much like an illdrawn Christmas card as anything.” And then referring to Degaldoruwa. Coomaraswamy wrote: “ … here are a series of paintings of great artistic and historic value; and if they are once destroyed or injured by complete or even partial repainting, nothing can replace them. These are the best paintings I have yet seen in Ceylon, but there are many other good ones, that is, so far as they have survived the danger of repainting work often entrusted not even to traditional Kandyan craftsmen, but allowed to be done by men from the towns or the lowcountry …”

DEGALDORUWA. 18th century murals. (Archeological Department photograph)

These sentiments were echoed by Harry Pieris as recently as 1980, because nobody had listened to Coomaraswamy’s warnings. Manjusri lamented: “The saddest thing about … my work is that many of the paintings which I studied and copied and photographed over the years have now disappeared for all time. They have decayed, faded, been destroyed or overpainted. The daily decay and disappearance of our temple paintings is one of the greatest artistic losses of our time.” In the name of archeological conservation too, great violence continues to be done. Some works of the highest order survive, tenuously as it happens, but this is painting and sculpture serving a different purpose from what we are now discussing. The fifth century frescoes of Sigiriya – thought by some scholars to be portraits of members of the parricide king Kasyappa’s household and regarded by others as apsaras, mythical damsels of the heavens, besporting themselves at the abode of the gods on Mt Kailasa – are secular paintings-if you accept the first theory; images with certain religious implications, if you accept the other. They are, of course, among the most important examples of the art of Sri Lanka, upon which paeans have been lavished from the earliest days of their execution, known and admired, but alas, degraded for quite unworthy commercial purposes in more recent times. A few centuries later, in the 12th century, fresco painting of a more elaborate and sophisticated nature, exquisite in its craftsmanship, began to cover the walls of the Tivanka Pilimage, the Northern Temple, in Polonnaruwa. Manjusri in his book, Design Elements from Sri Lankan Temple Paintings (The Archeological Society of Sri Lanka, 1977), found The Descent of the Buddha from the Tovtisa Heaven the most striking. “The Tivanka panels show what we might call a revolution in the painter’s approach and attitude to the world around him. For the first time we see in Sri Lankan painting the broad appreciation of values other than religious. The painter’s frame of reference has now become much broader …”, he wrote. Thus was given to what might have remained austere lessons in Buddhist philosophy a new, humanist dimension.

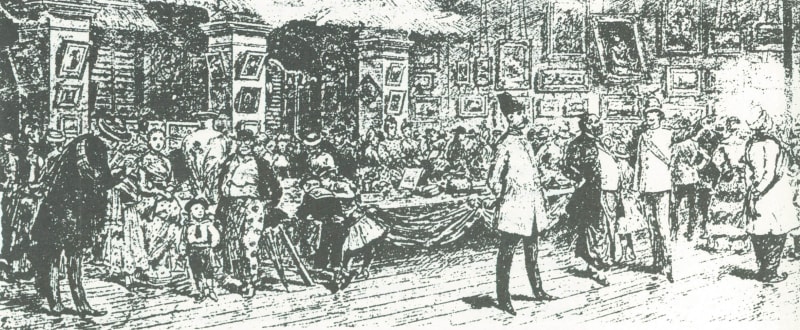

THE FIRST AMATEUR ART EXHIBITION. Colombo. August 1887

In both instances, at Sigiriya and at Polonnaruwa, the artists remain anonymous, as indeed do the sculptors of the few extant Buddha images of Anuradhapura dating back to at least 200 years before Christ, the fifth century colossi of Aukana and Sasseruva, the stone groups so exquisitely carved out of the living stone at the Gal Vihare in 12th century Polonnaruwa, and other works. However, so far as the fresco painting goes, Manjusri elsewhere was keen to establish that they were the products of the one school though separated by some seven hundred years. He argued, in a series of articles in the Ceylon Daily News in the early I960s, that there must have been a continuity of craftsmanship though there are not now too many examples to be shown in proof that Sigiriya and Polonnaruwa were not two isolated expressions of such outstanding skill. Coomaraswamy suggested that there were two contemporaneous styles of painting from early times. It helped to explain the sophistication of Sigiriya (or the Tivanka Pilimage), and the seemingly unschooled and primitive quality of some other work from quite distant antiquity.

The modern and particularly Western notion of painting came to Sri Lanka mainly in the years following the fall of the island to the British. Of Portuguese or Dutch activity of this kind there appears to be no evidence. But with the final intellectual and emotional colonisation which began in 1815 the people started to imitate the manners of the conqueror – framed pictures appeared on the walls, portraits were enthroned on easels, and a new psychology expressed itself in the way the ancient skills of the painter were employed. This was a new order of secularism. Easel painting had been discovered.

The Colombo Drawing Club, sometimes known as the Portfolio Sketch Club, was formed in the early I880s. Its members met in each other’s homes once a month, their portfolios were circulated, the work discussed and voted on, and the best for that month picked. The first exhibition was held to mark the diamond jubilee of Queen Victoria, in what was apparently a popular venue. It took place over four days in a holiday period known as Race Week, from 16 August 1887. The Ceylon Observer was most impressed and wrote: “With such a prestige as could hardly fail to ensure a successful inauguration, the Ceylon Art Exhibition rooms, situate for the nonce in Prince Street and above the Coffee Tavern, were thrown open to the public yesterday evening. The occasion served to bring together a large number of local artists, many of whom, perhaps, had hitherto not been known beyond the circle of their own acquaintances; and that they met with favour, and some received every encouragement from their patrons, goes without saying. Now that an additional item – and that a most attractive one – has been placed on the card of the Season, there can be little doubt that the event with prove an annual one …”

TIVANKA PILIMAGE detail. Fresco. 12th century Polonnaruva. Studio Times photograph

From such genteel beginnings came a second exhibition, not as predicted but two years later, this time in the Legislative Council Chamber; and, thus the Ceylon Society of Arts, “to encourage pictorial art”, was born. The resolution to inaugurate the society was adopted on IO December 1891 at a meeting held in the Committee Pavilion of the Agri-Horticultural Show. The first president was Sir Edward Noel Walker, and the inaugural exhibition was held under the auspices of the Ceylon Society of Arts in the Public Hall. It was formally opened by the Governor, Sir Arthur Havelock, on 7 December 1892.

Quite clearly, imperial Britain had made a forceful impression upon Sri Lanka, the new colony of Ceylon. It had successfully set up a system of privilege, and the native who responded with loyalty was rewarded. So much so that by the time the Ceylon Society of Arts had been set up, it consisted not entirely of expatriate Britons, but some, indeed, who were Sri Lankans. These had been educated in schools established primarily for the purpose of moulding employable clerical and administrative servants. And such, indeed, was the curriculum of these schools that a liberal education demanded that they become acquainted with all the extra-mural activities of those they were to serve. Piano lessons, for example, were mandatory for young women – but not for men, for whom it was considered too effete an interest. The new creature to emerge from this was the totally incongruous westernised oriental. Such was its curious outcome that many Sri Lankans still converse with one another in English and are unable to use their own language. In a letter to me, Harry Peiris said: “I wish I knew my own language (Sinhala) as well as I know English. What a lot of good I could have done in my field of work. I still try to improve my knowledge of Sinhala though it is very difficult to do so in the environment I am in … The advantage (Dr G.P.) Malalasekera” – himself a leading protagonist of the Ceylon Society of Arts – “had over others here was he was proficient in both languages. He also knew Sanskrit and Pali well. When I returned to the island (in 1938) I often discussed translating foreign literature into Sinhala with him. At that time I had not sufficient money to do anything worthwhile so the matter ended. I hope the Sapumal Foundation (See Appendix C), will soon be in a position to do what I was unable to do.” Harry Pieris supported the idea that an adequate literacy required the acquisition of at least two languages, one of which needed to be an universally spoken language other than the mother tongue. But to return to painting.

Unfortunately, what the Ceylon Society of Arts entrenched was a manner of painting that perpetuated the tastes and ideals of an English middle-class that was embarrassingly simplistic, often sentimental and at best naive. John Berger, the art critic of the New Statesman, in an introductory note in the catalogue of the first ‘43 Group exhibition in London in 1952, said it was “not only boring and dead but also an imported if not imposed art: an art deriving from the nineteenth century English tradition with an exotically ‘oriental’ overtone added.”

Thereby hangs our picture.