Richard Gabriel (19 February 1924 - 19 February 2016)

Chapter XI

The Simple Life

Gabriel’s hosannas

Richard Don Gabriel first appeared before us on the back of a brand new bicycle sometime in 1944. At the age of 20 he had just been appointed the youthful art master of St Joseph’s College, Colombo, while it survived in wartime exile, partly in thatched classrooms, on the grounds of the Archbishop’s palace in Borella, the present campus of Aquinas University College. He was the product of the religion into which he had been born in 1924, the Catholic schools he attended, and the company in which he found himself. Through his brother Edmund, Gabriel came to know Ivan Peries, himself a Catholic – and all at one time or another students at St Peter’s College, Bambalapitiya. Ivan Peries encouraged him to paint. The result was that when the year 1943 came around it was only meet and just that Richard Gabriel be invited to join in the founding of the ‘43 Group. In the beginning he worked under Ivan Peries who soon took him to Harry Pieris with whom Gabriel enjoyed a lifelong master-pupil relationship.

GABRIEL: The Artist’s Mother. Oil on canvas (51cm x 66cm). Collection: the artist

Gabriel tells his story: “It was my brother Edmund who introduced me to Ivan early in 1941. If not for my brother, my life would have taken a different path. The picture, the first I was to show Ivan, was a black and white water colour of my father whom I had not seen except in the wedding photo, and in that he was seated. I had a curious notion that my father had an artificial leg – this may have been because I had not seen him in a standing pose, so I made him stand in my picture. When Ivan saw this he wanted me to come and see him whenever I was free. (I was still attending school). Ivan did not give any practical lessons but his talking or lecturing was more important since I knew nothing about art or of artists. The only names I knew were Michelangelo, Raphael, etc, from the standard history book … At this time there was to be a War-Effort Exhibition organised by the Information Department. Ivan gave me some old canvas which I cleaned up and did some work – four of them – and to my surprise I won four prizes. Impetus, indeed, for a schoolboy … My mother was the one most elated that I was interested in painting. Not a surprise. I remember that she used to do a lot of pillow-lace and crochet work. All the curtains and bedspreads were her handwork. She had a fine sense of design. After the war effort exhibition, urged by Ivan, Harry asked me to come for lessons. He knew my financial position and did not charge a fee … After a year or so, I was the only pupil left: Harry ha~ asked the others not to waste his time or their parents’ money …”

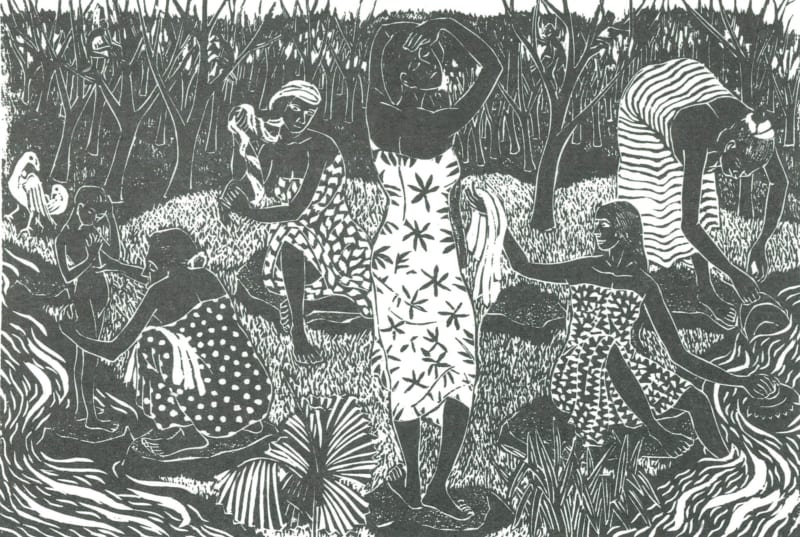

GABRIEL: By the River. Woodcut (46cm x 30cm)

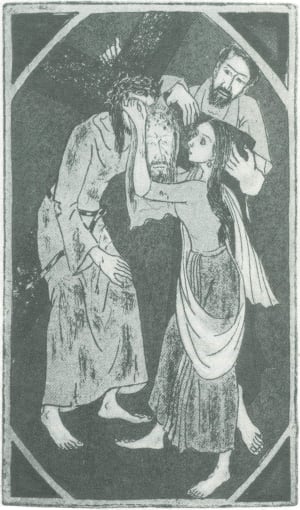

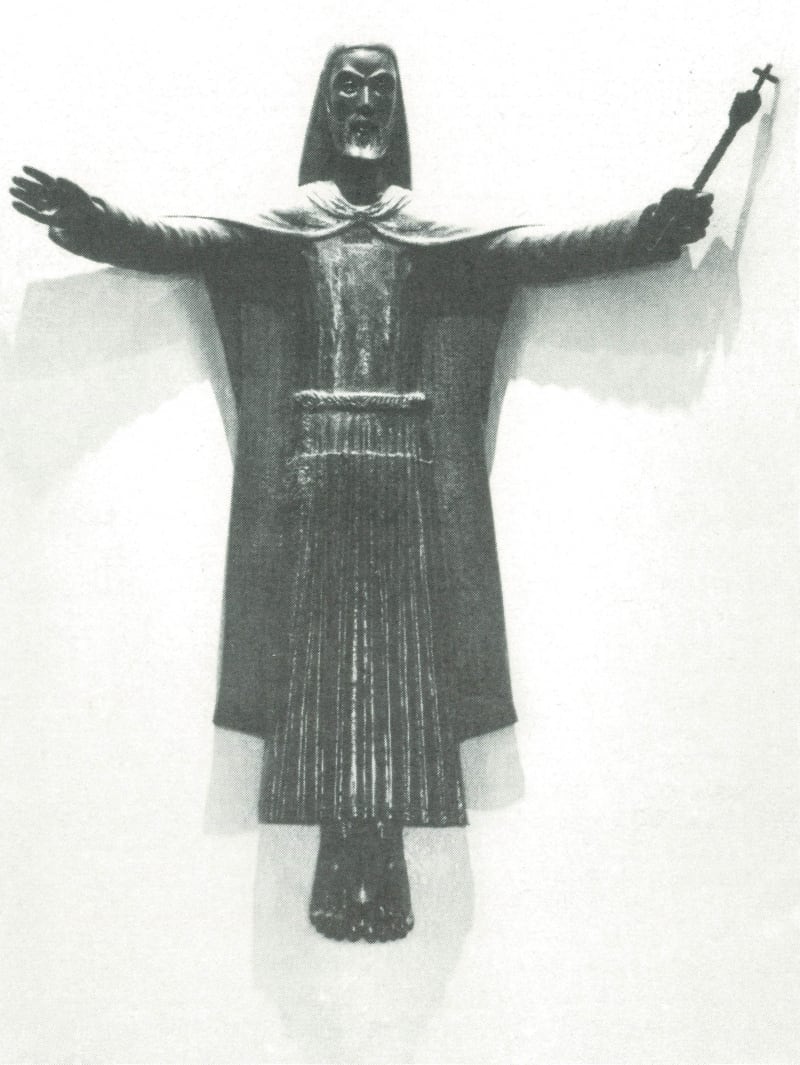

His religious background explains many facets of his work, among them the murals and the bas-relief Stations of the Cross at St Therese’s, Thimbirigasyaya; the Risen Christ carving which dominates the sanctuary of the Jesuit chapel in Bambalapitiya; the eight-and-a-half-foot high Madonna carved for the National Seminary in Ampitiya, Kandy (which has suffered considerable ignominy at the hands of at least one incumbent rector): murals at his parish church of Christ the King in Pannipitiya: and his book of etchings dedicated to death and known as The Cross, completed in 1975, using a technique learned in one short afternoon from Rani! Deraniyagala. This collection of etchings came as a surprise to me because Gabriel has always been the painter of the tranquil landscape in which his people blended harmoniously with their own rich environment. He was ever zealous for a quality of life that was gracious and was deeply devoted to tradition. This preoccupation with death seemed morbid.

GABRIEL: Before the Entombment. Oil on canvas (173cm x 120cm). Collection: the artist

The book was an edition of 33 numbered copies – one for each year of Christ’s life on earth – each hand-bound by the artist in deep red leather, with legends and devices embossed in gold leaf. The book measures 23 cm x 31 cm. The etchings themselves are considerably smaller, mounted on textured papers. After the title page come the fourteen Stations of the Cross, hand-printed in sepia. The concluding etching is of the Resurrection, also printed but in glorious colour from a single copper plate in which certain segments had been cut out and inked separately – a highly involved and. I believe, original technique. The Resurrection etching is an affirmation of his hope and of his faith. I read the book of etchings at the time as a kind of final testament, and I had no doubt that Gabriel had the experience to discuss the ramifications of life and death. But, of course, this was no act of resignation. It is a statement rather, of belief, an act of faith in the deepest Catholic tradition.

GABRIEL: Veronica and Jesus. From The Cross, a book of etchings.

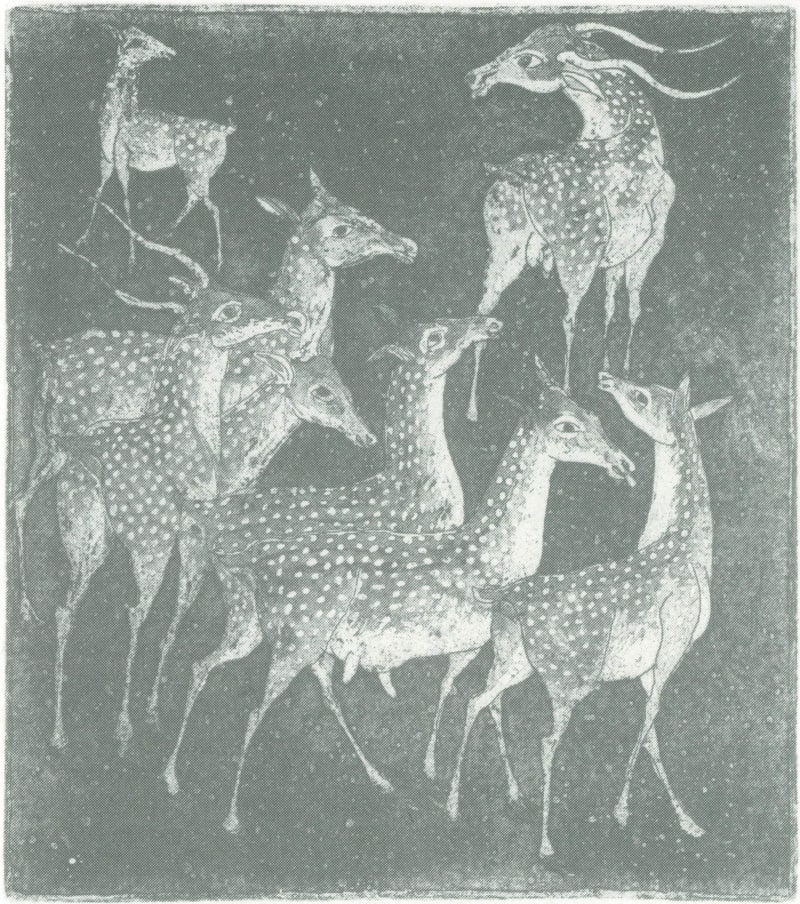

His enormous output at the easel, his powerful work as sculptor in wood, as muralist, and now printmaker was evidence enough of a lively mind. I was concerned by the timing of this book of etchings. His work had never been so disarmingly direct, though you might have argued that he had an equally disarming naivete. Gabriel understood the aspirations of the common man as a reaching out for the simple, idyllic life, where freedom meant freedom to dream, to be still, to be like the birds of the air, neither weaving nor spinning but arrayed in a certain grandeur. This was an ideal that suited Gabriel’s concept of Christianity. Humanity had been redeemed after the fall and was now at peace, an Utopian peace perhaps, but peace nevertheless, placid, graceful, quiet people pursuing their ordinary and ordained tasks, fishing and ploughing and gathering their nets and their harvests after them: and then they rested from their labours. Yet Gabriel was always aware of the incessant struggle to maintain that Utopian peace. Symbolising that struggle was the conflict between man and beast. They appeared in numero.us compositions in vigorous opposition, perennial antagonists. Not only was there conflict between man and beast but conflict among the beasts themselves, the animals providing a marvellous opportunity to explore movement as bulls clashed against each other and stag gored stag.

But images alone are not the stuff of art. Gabriel’s work is remarkable for its sense of order and discipline. This is the kind of order which disciplines the image, conforming almost mathematically to the scholastic argument for order and harmony as against chaos and outer darkness. His work is marked by strong, brisk drawing, and fluent, energetic colour – exquisitely demonstrated in Fighting Bulls purchased for its permanent collection by the Musee Petit Palais in Paris at the exhibition of the Group there in January 1953. The Petit Palais acquisition vindicated, if that was necessary, the quality of Richard Gabriel’s art.

GABRIEL: Spotted Deer. Etching (17.5cm x 20cm)

He was noticed in the first exhibition of the Group in 1943 as “an artist of promise.” The following year, the Times of Ceylon found that he was “developing extremely well: his work looks like nobody else’s, and will generally be rated very high. His selfportrait complete with crucifix … should have hung alongside A. C. Collette’s ‘43 Fresco caricaturing the Group around its unofficial Diaghilev.” At the fourth exhibition of the Group in 1947, Gabriel was observed as “imaginative and ambitious”, offering two large canvases on a religious theme. He was found to be more acceptable in Thirikkele Race, and Two Horses. Another critic was quite devastating in his opinion: “I can see no justification for the presence of (Gabriel’s) works in this exhibition. The ‘43 Group cannot be taken seriously if it allows as exhibits trivial schoolroom exercises … Gabriel is an artist obviously experimenting with the modern without really knowing wh-at it is all about. For instance, he disregards perspective without providing a convincing substitute. He aims at freshness of colour but only succeeds in making one uncomfortable. The best one can think is that he has not yet found his medium.” This overwhelming appraisal was signed by A. C. L. whose identity continues to elude me. Jayanta Padmanabha was just as sceptical: he found Gabriel’s Resurrection “a pretty piece of devotional decoration by El Greco out of Walt Disney.” He mentioned it, he said, not because it was essentially bad but because it was at the opposite end from Justin Daraniyagala’s Maternity which he could not abide – evidence of disparity not diversity, “representative of the whole Group.”

Geoff Beling, as chief inspector of art in the Education Department, wrote that one of the special features of Gabriel’s work had been its consistency. “A consistent worker, always drawing and painting, Gabriel has maintained his own vision and expression in terms of the life of Ceylon.” Beling was also able to assess Gabriel’s contribution as a teacher, and in an essay written for the St Joseph’s College magazine for 1949, remarked that “the exhibitions of school art at St Joseph’s, like those at Royal (College) in the time of Collette, have been one of the aesthetic delights discerning people in Colombo have enjoyed year by year.” Beling said: ‘Art at St Joseph’s under R. D. Gabriel reveals a maturity that is not possible without (able) guidance Year by year there has been a new discovery of talent at each exhibition and a promise of future development …” Of Gabriel, the artist, Beling wrote: “He is a true artist, not working for money, fame or popularity, but seeking the solution of aesthetic problems that interest him and reflecting in his work the sin€erity and humility that come from his unassuming nature.”

GABRIEL: Bathers. Oil on canvas (152.5cm x 96.5cm). Collection: the artist

Richard Gabriel won a British Council scholarship in 1952 and was enrolled at the Chelsea School of Art, London, where John Berger, a most enthusiastic critic of the Group, was a lecturer. Gabriel was accompanied by his wife. Sita Kulasekera. They spent most of that year and the next there and travelled with Ranjit Fernando to Paris in the course of preparations for the Group’s exhibitions in Europe. In his review of the work of the ‘43 Group at the Imperial Institute Maurice Collis observed in Art News and Review of November 1952 that the Group was a reaction to Edwardian academism. He wrote: “A synthesis between European modern painting and oriental classic or folk art is rightly the objective, as only thus can a modern Asian art be brought into being.” He observed that such a venture could only succeed when the artists participating had the skills to undertake it. In this context he found that Gabriel’s Thirikkele Race (translated here into Bullock Cart Race) was “as rich in its textures as an early Adler, a really choice piece of craftsmanship which shows how thoroughly the artist has studied the technique of painting.” The critic on the Manchester Guardian saw in the “dark and blood-stained Crucifixion by Richard Gabriel a Grecolike figure to the right of the canvas which reminds one also of the figures from the Ajanta caves …” William Graham in The Studio found Gabriel “a painter completely devoid of theories, conveying a primitive poetry of Ceylon with delightful fancy.”

GABRIEL: The Risen Christ. Wood (244cm high). The Jesuit chapel, Bambalapitiya

Some years later, at the tenth exhibition of the Group in Colombo, Fred de Silva in The Times of Ceylon of 2 December 1955 suggested that Gabriel was indeed, challenging the Big Three – Daraniyagala, Keyt and Harry Pieris. “It is clear that Richard Gabriel must very soon qualify to break up the trinity. The Family, a luminous yet casual group of ordinary people is an outstanding example of his craftsmanship and refined sense of colour. It is quite the most arresting picture on view. The family – man, woman, child and goat – are superbly grouped in attitudes of quiet listlessness but with a compelling and intimate sense of unity, an unity at once familiar and en famille. Truly a study in compassion. Several other pictures … show that Gabriel is the only considerable painter of the Group blessed with a palette and an idiom capable of recording the beauty and significance of everyday life.”

In proper recognition of which, in 1964, the Florentine art academy – founded in 1564 to honour Michelangelo – breaking with known practice, conferred on Gabriel the distinction of honorary membership. L’.Accademia Florentina della Arti del Disegno was celebrating solemnly its four hundredth anniversary. Gabriel thought the academy had his series of woodcuts in mind when it made the award.

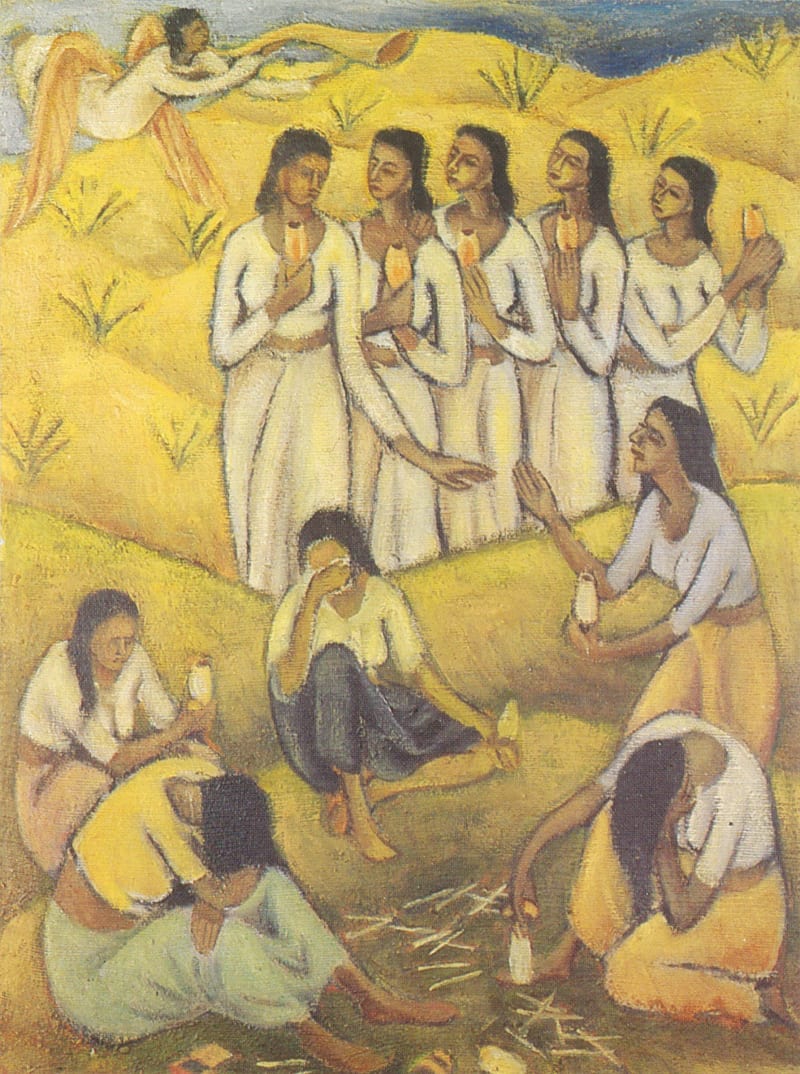

GABRIEL: The Wise and Foolish Virgins. Oil on canvas (51cm x 67.5cm). Collection: the artist

Taking a retrospective view of his work at an exhibition arranged by the Alliance Francaise in Kandy in 1988, Professor Dissanayake remarked that after nearly fifty years of practice as a painter “his vision and methods and materials remain unchanged:’ Gabriel would quite agree with that statement. It is a matter of great pride with him that he has been loyal to his beliefs, in art as in religion.