George Keyt (14 April 1901 - 31 July 1993)

Chapter XII

The Spiritual Voluptuary

The Keyt predilection

When George Keyt came to have lunch with us in Bambalapitiya many years ago, he wore two wrist watches. Naturally I was intrigued by this and wondered what kind of metaphysical explanation he would have given had I asked him why. After some argument within myself, I decided there must be a good practical reason, because Keyt is, above all, a good reasonable man. He was fully aware of his capabilities and his responsibilities as an artist. “Sarasvati,” he said, “has not left me. She is still at my elbow.” And with the blessings of the goddess of music and art, Keyt has continued to dominate the world of painting in Sri Lanka as he has done every exhibition of the ‘43 Group – indeed, wherever his pictures were hung. The colour was always brilliant and remarkably balanced, the drawing actively engaged in binding together all sorts of elements. At most times they were a hymn of praise to the beauty of the female figure. He was in ecstasy over it. In time, Keyt was to discover through Hinduism a rationalisation which gave a spiritual dimension to the purely physical delight. He was able to luxuriate in the Krishna myth; the Gita Govinda provided a sacred text. That epic period began in the thirties.

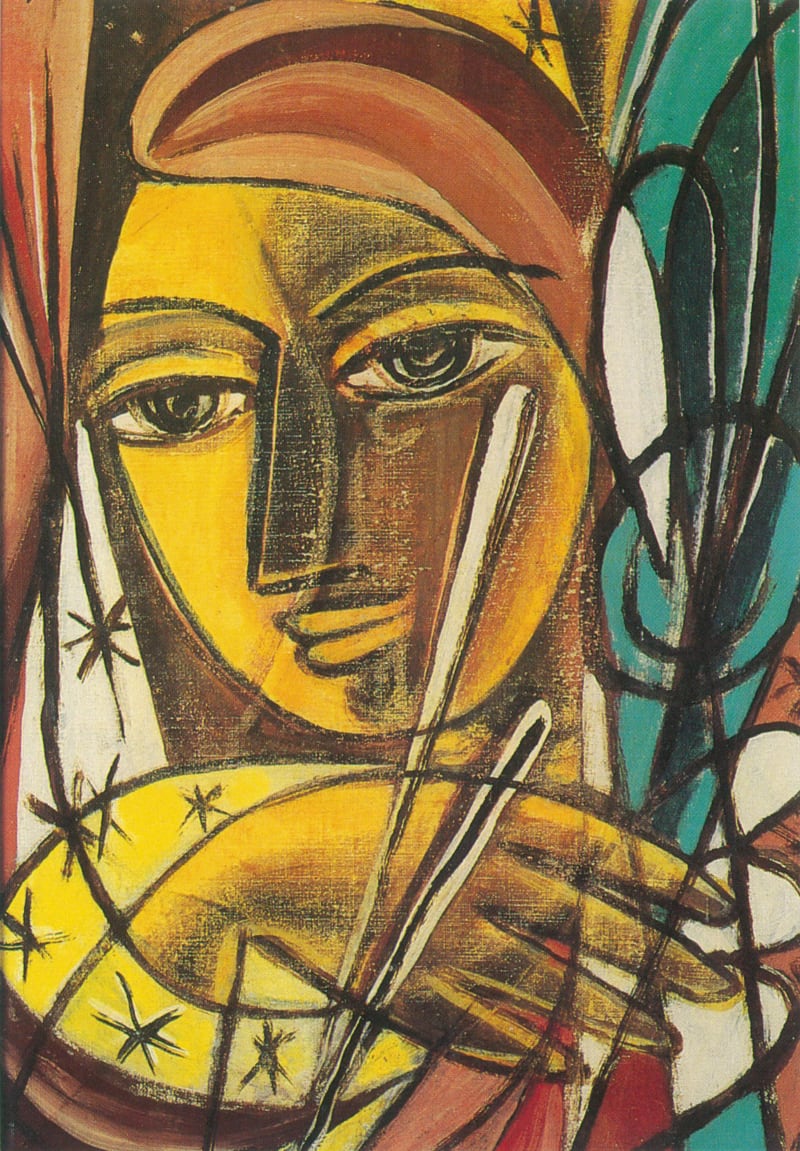

KEYT. Nayika. Oil on canvas (28cm x 42.5cm). Sapumal Foundation

A decade before in his native Kandy, George Keyt had become acquainted with the Buddhist revival. When it was still quite unfashionable to do so, he visited the Malvatte monastery where he studied Buddhism and Sinhala and became familiar with the furniture of the temple – brass objects, ola leaf manuscripts, palm fans, and so on – which he learned to use in still life compositions. He became intimate with the ambience and atmosphere of the vihare. He painted pictures of Buddhist monks including a portrait of his friend, the Yen. Pinnavela Dhirananda Thero. Very soon he affected the dress of the East. Draped in dhoti and kamiss he made a statement which challenged the English-speaking middle class.

Cover for catalogue. 1952

Keyt’s career as a painter stretches over sixty years, beginning about 1927 when he was 26 years of age, encouraged by Lionel Wendt whose advise Keyt’s mother had sought. Wendt had the resources for obtaining all the colour prints and art magazines of the time, containing reproductions of Picasso, Matisse and Leger, which were to help Keyt as well as Beling in their search of a suitable form for their work. Beling recalled, in a television documentary by Willie Blake to mark Keyt’s birthday in 1985: “Wendt was a remarkable man. He was always interested in developing the talents of other people, so he set out to develop my talent and Keyt’s talent, and he organised the exhibitions.” Together, Keyt and Beling were to become early pupils of Charles Freegrove Winzer, the government inspector of art. (I have referred to Winzer earlier in this account)?Keyt and Beling exhibited together and Winzer applauded them in a short note which appeared in the January 1931 edition of The Studio, the British art journal. Of Keyt’s work, Winzer said: “In Keyt’s canvases the attitudes and gestures faithfully portray the characteristics of the inhabitants of Ceylon. The subtly rendered gradations of flesh tones going from pale gold to dark brown are intensified by the deep or vivid garments; occasionally the harmony is one of greys and browns with the acid pinks so typical of southern India adding an unexpected distinction to the colour scheme.” There were many points of similarity in their work, particularly in the paint quality and in the way the mass was distributed within the canvas though, as Winzer pointed out in The Studio account, they remained “by their choice of motives, composition and colour schemes entirely individual.” Indeed, Beling’s approach was austere and abstracted while Keyt already displayed his now well-known enjoyment of the graceful curve. In Blake’s television documentary Beling paid tribute to his contemporary: “Artists are not made; they are born. George Keyt was born an artist … He is a great painter. He knows how to compose. He knows how to organise his pictures. All his pictures have what is called aesthetic or significant form without which a work of art is not a work of art. Keyt belongs to the higher order of really major artists, creative artists. He was not recognised for a long time in Ceylon but I believe he has now an international reputation. And he utterly deserves it. You have to see the , monumentality of his work to understand what he has done. His whole lifetime has been devoted to art and the monumentality of his work is seen only when you view it from his early days to his latest paintings. His art is really first rate; beautifully composed, a wonderful sense of colour, in an idiom that is his own. You can’t mistake his work for anybody else’s. His work is unique.” Beling said: “Keyt once described himself as a spiritual voluptuary. I suppose it was the voluptuousness of Indian art that attracts him.”

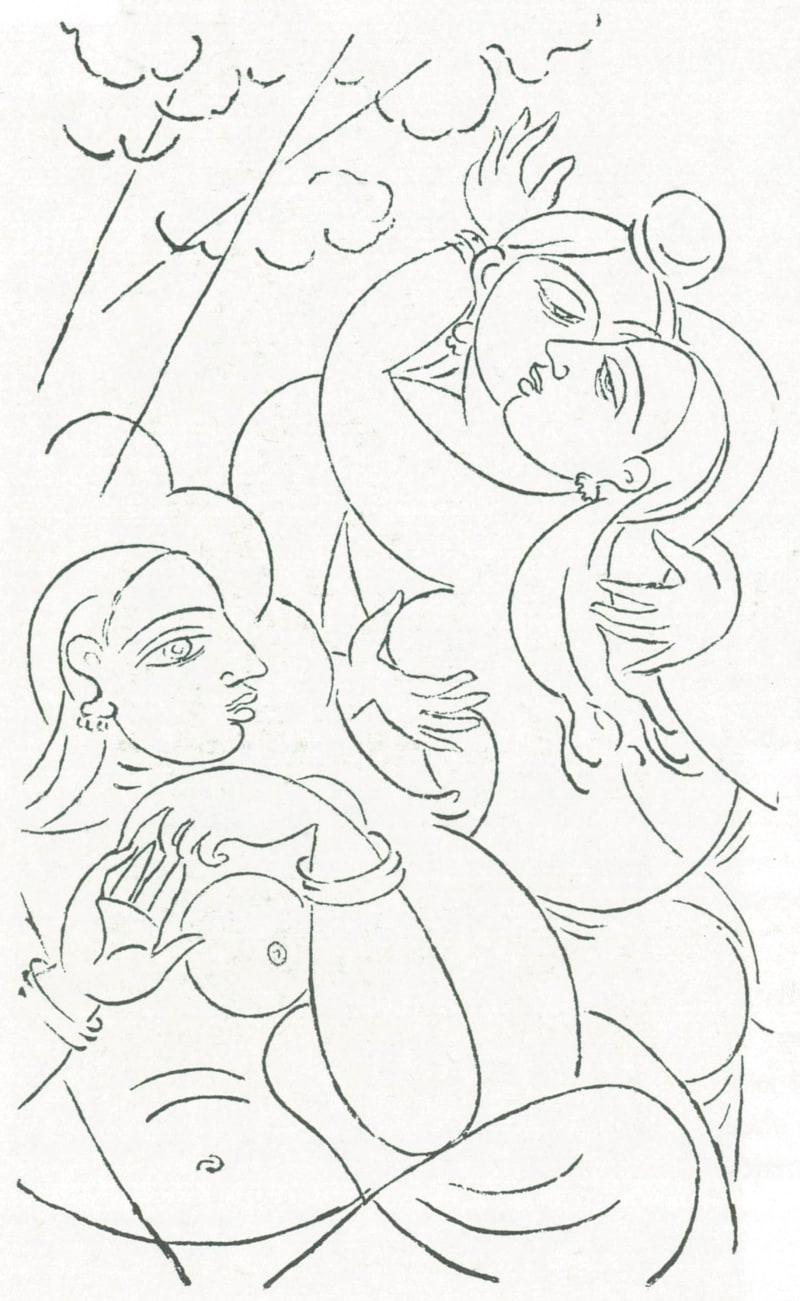

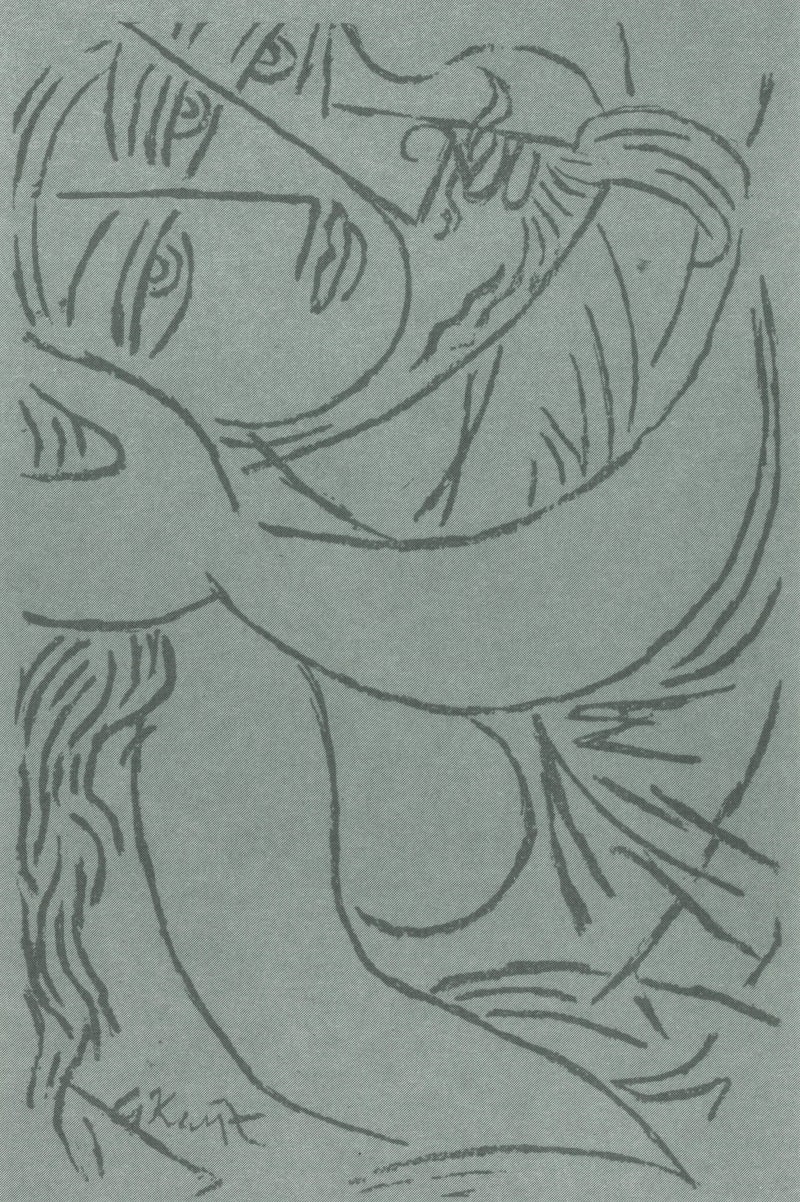

KEYT: Gita Govinda illustration

There are substantial elements that make up this monumental picture. It begins with Keyt’s childhood fascination with certain Christian images – the Holy Family, for instance, and the Crucifixion. Peggy Pieris. Keyt’s sister, said he had been obsessed with the Crucifixion. If that was a passing phase, he was not to begin painting seriously until he was 26 years of age when he turned to the countryside that nurtured him in his childhood and youth. The Kandyan landscape and the Kandyan people became his subjects; and soon too, the temple to which he turned, instinctively, to study the religion and the language of the people. To rationalise his great predilection for women he turned to things Indian generally and the Hindu thought that saw in the conjunction of the sexes a participation in the divine creativity. He found eroticism enthroned as a philosophy. India’s epics spoke of it and so did India’s poetry, and the sculpture of ancient India was explicit. “They made a tremendous impression on me and changed my whole life.” He visited India first in 1939, and was to keep returning there from time to time. In the middle thirties, following a period of aridity which he attributed to an emotional crisis, Keyt abandoned urban life to live in remote villages in the hills of Kandy. In the fastness of Harispattu, Keyt says, he had “no inclination to paint, and in order to give vent to my feelings I took to writing poetry.” These appeared as three volumes: Poems. Darkness Disrobed, and Image In Absence. Coming down from his retreat in 1938 he began the mural of the life of the Buddha in the Gotami Vihare at Borella in Colombo. Not true fresco but painted on dry white plaster, these murals remain by far the most extensive of their kind. They are very moving and truly magnificent, providing a splendid vehicle for the cubistic elements Keyt had discovered from modern Europe to combine with the resolute line of the East. However, there was something ironic about a masterpiece such as this which paid tribute to the ascetic resolve of the Buddha and which Keyt himself was to abandon. It seemed that in the isolation of the Kandyan hills he had communed with the gods who had revealed to him once more the beauty of their apsaras as they had done fifteen centuries before to the painters of Sigiriya. These creatures were now to become handmaidens to the artist. Here was an infinitely richer altar at which to worship.

George Keyt had thirteen pictures at the first ‘43 Group exhibition in November 1943, which intrigued one critic for their “geometry” and impressed another “by his dexterity with line, form and daring use of colour.” These were all bought by Martin Russell, as has been noted before, at the urging of George Claessen. Keyt continued to dominate exhibitions of the Group, but was not always applauded for his pains. Jayanta Padmanabha, for instance, in a March 1945 review said: “Mr George Keyt is probably the most gifted painter in the Group. He too goes in for abstraction in a big way,” (the other being Daraniyagala), “and much as I admire his fine draughtsmanship and his sense of composition and colour, I would not personally choose to live with any of his numerous geometrical amours or abstract reveries in design.”

KEYT. Sage and Girl. Conte on brown paper (24cm x 37cm). Private collection, Melbourne

By the time of the seventh exhibition of the Group in 1949, Tori de Sousa allowed for Keyt’s work being of “outstanding merit.” He confessed: “One feared that Keyt was becoming repetitive, that preoccupied with elemental technicalities of form, line and colour he was producing artificially mechanical exercises devoid of vitality or meaning. But one has only to see the rich profusion of Keyts on show here to realise that this is not so. They are fresh, alive, and exciting, and better than most of his work I have seen.”

The retrospective exhibition of Keyt’s work organised by the Group at the Lionel Wendt Art Centre in March 1950 was received with unanimous approval by the press. A small exhibition of 45 works, it attempted to trace the artist’s development over the first twenty years of his career. The critics acknowledged his achievement in the synthesis of traditional Indian and modern European painting. They saw that it had been a “liberalising influence.”

KEYT: The Life of the Buddha. Gotami Vihare, Borella, Colombo.

Another one-man exhibition was held in May 1952 which contained 74 paintings made mainly between 1942 and 1946. Fred de Silva of The Times of Ceylon took exception to an aphorism of Keyt;s quoted in the catalogue which defined “true painting” as an “emphasis, in its most unequivocal form, on line, colour and shape. But to those not literate in it, painting is as meaningless as any other foreign language though perhaps more tantalising.” Fred de Silva objected to the implication that you had to be specially educated in art. “Art has too important a function in the life of the community for its enjoyment to be restricted to a small circle of connoisseurs”, he said. “So, whenever I want to see the art of George Keyt I go to the Gotami Vihara and not to an exhibition.”

Keyt was greeted in London at the first Group exhibition at the Imperial Institute in South Kensington in November 1952 with the complaint that none of his important works had been included. John Berger believed that had Keyt’s work been known in Britain, he would “surely be recognised as an artist of important genius,” but wrote in 1954 that, well-known and important painter though he was. Keyt produced arrangements. “He gathers together elements from Picasso, the Indian cave paintings at Ajanta and the Sinhalese at Sigiriya … He lacks the fire to fuse the elements together because his mood is too nostalgic and his observation too schematic.”

KEYT: Gita Govinda illustration

William Archer, sometime curator of the Indian section of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, found that “a fervid appreciation of physical form, a passionate exploration of poetic romance and a certain close connection between his idioms and those of traditional Indian art” gave Keyt’s painting a strongly national character. Archer wrote the Introduction to the catalogue of an exhibition of Keyt’s paintings and drawings at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London.

William Graham writing in The Studio in 1954 found that “the genius of George Keyt lies in the wholly original manner in which he finds inspiration in ancient Eastern art. In Sinhalese and Indian mythology he has found themes capable of expressing a modern philosophy of life through his own emotional and poetic imagery. His work has a sensuous poetry, with frequent allusions to the ancient forms of song and dance, conveyed with a charteristically Oriental calligraphy.”

KEYT: Seated Nude. Oil on canvas. Mr & Mrs H. A. I. Goonetileke Collection

Reviewing the exhibition for Art News and Review. 23 January 1954. Peter de Francia found Keyt, “at first glance to be the most traditional of the (Ceylon) painters, his work deriving from Indian fresco painting, his drawing linear, his themes largely religious and mythological … His work is full of a formal sensuality, of a type that was hardly ever found in Western art, and completely lacking in any type of painting of the twentieth century.” A correspondent on The Indian Express was delighted with the Keyt drawings at the Gallery Chemould in Bombay in 1969. In the issue of 13 May he wrote: “Classicist in thought but modernistic in treatment, George Keyt first and foremost shows how tradition should be carried forward and interpreted. And the brilliance of his talent shines in every line as he cuts and sweeps in masterful style to recreate amorous couples in dalliance, or waiting with the weight of their passion for the hour of love. There is, of course, nothing blatantly erotic in George Keyt’s lovelorn portrayals: only a sensuous lyricism that warms the heart and creates a spell of beauty and delicate passion.”

KEYT: Raga Malkosh. Oil on canvas (125cm x 86cm). Shelagh Goonewardene Collection. Photograph by Amahl Weereratne

Keyt likes to tell the story of how, in January 1930, an exhibition of paintings by Beling and himself was to be hung in a hall belonging to a Christian organisation which objected to some paintings of the nude. Keyt relates that Pablo Neruda, the Chilian poet, who was there said: “That’s all right. They can hang them outside!” He gave the poet a painting which Neruda was to carry with him wherever he travelled. He wrote: “Keyt, I think, is the living nucleus of a great painter. In all his work there is the moderation of maturity. Magically though he places his colours, and carefully though he distributes his plastic volumes, Keyt’s pictures nevertheless produce a dramatic effect, particularly in his paintings of Sinhalese people. These figures take on a strange expressive grandeur, and radiate an aura of intensely profound feeling.” Keyt was highly regarded in India. He went there for the first time in 1939. In 1945 he visited Bombay as a guest of Mulk Raj Anand and Anil de Silva, and was given a one-man show in 1947. He kept returning to India from time to time thereafter. He told The Free Press Journal in Bombay during a 1969 visit that he considered India his home and that he took pride in his Maharashtran ancestry.

Sri Lanka, however, regards him as her own living treasure, and embraces him firmly to her breast.