Lionel Wendt (3 December 1900 - 19 December 1944)

Chapter V

A Focus On Art

The Wendt contribution

There was buried in the foundations of the house that Lionel Wendt built at 18 Guildford Crescent a scroll on which he wrote: “May all honest endeavour in the service of beauty flourish therein and win its reward of inward content and the peace that is only in ceaseless effort.” It is to this house, now enlarged into the Lionel Wendt Memorial Arts Centre, that thousands flock in search of that inward content and peace. That story is an odyssey in itself, but it contains part of our present narrative.

The walls of that house were covered with the paintings of his friends and proteges, large canvases by Keyt, still life compositions and landscapes by Geoff Beling, Winzer’s work and great enlargements of Wendt’s own photographs. Dominating the floor was the grand piano at which Wendt is seen dressed in a flaming dressing gown in the portrait by Beling. Lester James Peries has a colourful picture of Lionel Wendt. In the pamphlet for the 1991 Keyt celebration. Lester Peries described Wendt as “a large man, a hulk of a man. Smoked a foul brand of cigarettes endlessly. He wore braces all the time to prevent his pants from falling off. He had a huge tummy which would shake and roll as he laughed. He generally dressed in multi-coloured shirts. Lionel Wendt was a marvellous speaker – he was the greatest raconteur and witty conversationalist I have ever known, not excepting Cyril Connolly and Harold Acton whom I have seen in action. One can only suggest the wit and the flavour and the sparkling ironies and, of course, the obscenities which were the funniest part of his conversation … At the same time, everybody respected Lionel Wendt so deeply that they listened to him. Nobody wanted to impair his vision. Even Justin (Daraniyagala’s) torrential verbal onslaughts were stilled. George (Keyt) was compliant. Nobody thought it was beneath his dignity to hang with the others.”

SELING: Portrait of Lionel Wendt. Oil on canvas (65cm x 75cm). Lionel Wendt Memorial Trust

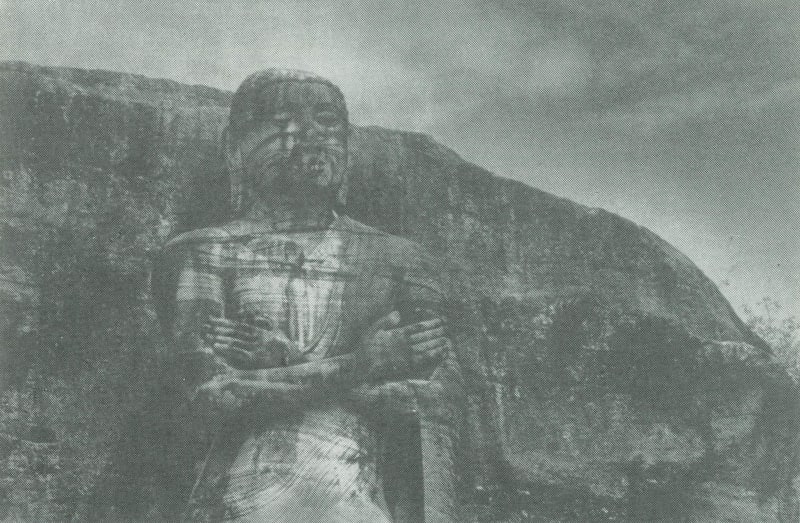

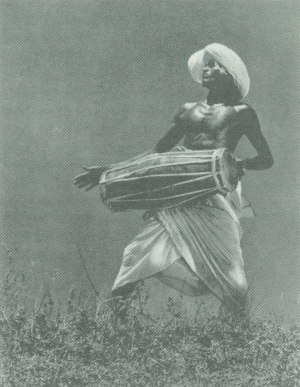

Wendt’s influence was very broad and spread generously about him. On a visit to Sri Lanka in the late sixties, Basil Wright who made the now highly acclaimed documentary. Song of Ceylon, acknowledged freely that without Wendt there would have been no film. Quite simply, Wendt took Basil Wright by the hand and revealed to him some of the images that made” Song of Ceylon (1934-35) so beautiful. Wendt led the GPO Film Unit to the Gal Vihare in Polonnaruwa which offered so powerful and constant a motif in the film, and to other parts of the country. He introduced Wright to the dancers of Nittavela. The documentary made innovative use of montage in an inspired juxtaposition of sound and image: and it had a wonderfully imaginative film score which cunningly absorbed the rhetoric of the gajaga vannama. The narrator’s voice is that of Lionel Wendt who made two short visits to London for the recordings taking the drummer Suramba with him. Lloyd de Silva, a member of the triumvirate which ran the Colombo Film Society in the forties and fifties, said that Wright on his last visit gave people who met him enough hints to form a fair picture of Wendt’s contribution, apart from his reading of the commentary. “When the 25-year-old Wright arrived in Ceylon in 1934, all he had was an introduction to Wendt … Obviously Wendt took him everywhere his interests led him. The material was largely of Wendt’s choosing: you have only to look at his photographs and the film to see his guiding hand.”

Wendt had the leisure to pursue these interests because he was a man of independent means, though he observed the conventions of the time by gaining professional legal qualifications, in the event like those of his father, Mr Justice Wendt a lawyer and judge of the Supreme Court of Ceylon. Lionel Wendt was able to turn his mind in due course to the pursuit of other matters. That included a vigorous enjoyment of modern painting as has been mentioned already. His visits to Europe for his studies, (he joined the Inner Temple, London, in 1919 and became a barrister: he also studied music), had proved to be a means of constant renewal.

The middle thirties coincided with the making of Song of Ceylon and with Wendt’s role in what W. J. Archer considered decisive in the growth of the art of George Keyt. In his chapter on Keyt in India and Modern Art (George Allen and Unwin, 1959). Archer writes: “Like Rabindranath Tagore and Amrita Sher-Gil, Wendt had visited Europe, had seen examples of modern painting and had also imbibed something of Western vitality. He was to stand, in fact, to Ceylonese painting in the same relation as the photographer Man Ray stood to French. Wendt undoubtedly played a crucial role in Keyt’s development – partly by encouraging him with patronage, partly through his passionate adhesion to modern art, but perhaps above all, by acting as a stimulating purveyor of modern artistic ideals.”

L. C. van Geyzel in his Introduction to Lionel Wendt’s Ceylon (Lincolns-Prager. 1950) draws the neat conclusion that although Wendt had been called to the Bar and had practiced for a while. “it would seem that he had to be an artist and nothing else, and only then could his remarkable talents come into play.” Among them, and pertinent to this account, was his capacity to hold together the highly individualistic persons who made up the ‘43 Group.

Wendt was an accomplished pianist. He had studied at The Royal Academy with Oscar Beringer and with Mark Hambourg in Berlin. He had a deep interest in the piano music of Bela Bartok whom he studied incessantly, but which he did not perform in public. However, at public concerts given by the Ceylon Music Society in his house, Wendt performed mainly in duos and trios with his principal pupils, among them Hilda Naidoo (nee Weerasuriya). He delighted too. Len van Geyzel tells us, to play for his friends, anything “from Beethoven to boogie-woogie.”

At about this time, in the middle thirties, Wendt was looking for an appropriate means of interpreting the country and her people. Len van Geyzel places this search in the context of a growing discontent and wrote: “The present is an age of revaluation. The values of Western culture, dominant for centuries, seemed to need revitalising. Here to hand in Ceylon was a way of life that was very old, but which retained, in spite of poverty, squalor and apathy, a vital sense that was lacking in more progressive countries. Man, living in traditional ways, had not become alienated from his environment.” Wendt turned to this landscape and these people with his camera. In 1938, he held a one-man show of his work in London sponsored by Ernst Leitz of the celebrated Leica company. Van Geyzel recalls that Wendt’s interest in photography began sometime after he had moved into his own house in Guildford Crescent when “he happened to pick up a cheap camera somewhere for a couple of rupees, and soon he was clicking away with the abandon of the happy amateur. The more successful results would be sent to his friend. George Keyt, who worked at the time in a photographic studio in Kandy, to be enlarged.”

When Lionel Wendt died at the age of 44 on 19 December 1944, it was slyly predicted that it spelt the end of the ‘43 Group. The Group, however, marked the event with its third exhibition and dedicated it to Wendt. It took place from 17 to 25 March 1945, appropriately enough in the Photographic Society’s rooms in Darley Road where the earlier exhibitions had been held. One newspaper commented that “taken all in all, the show falls short of the standard of the previous exhibitions … (However), the show should not be missed, if only for the fact that it is dedicated to the memory of a truly great artist – Lionel Wendt, who sponsored the cause of progressive art in this country and was the ‘moving spirit’ of the ‘43 Group.” 1\vo paintings were dedicated to Wendt: they were Justin Daraniyagala’s The Memoriam, and Ivan Peries’ Homage to Lionel Wendt. The critic’s comment on them was that “the former (Daraniyagala) reveals once again his powerful skill as a technician, a master of colour, balance, line and form; but the more successful and intelligible of the dedication is that of Ivan Peries, who handles the theme with much poetic feeling. His picture (two tree trunks, the sun and sea and earth),is almost a monochrome with a feeling for power, attitude, space and immensity, vivid and vast. There is a note of timelessness and brooding in this tribute.”

STANDING BUDDHA. Gal Vihare, Polonnaruva. Photograph by Lionel Wendt

It is interesting to observe the changes that took place in the list of exhibitors with this show. Manjusri Thero was absent, having resigned earlier, and S. R. Kanakasabai and Yolvin Thuring who had been invited to take part in the inaugural exhibition did not exhibit. In their place, new to the Group, were Edmund Blacker, Gordon Davey, Ivan M. Fernando, P. Guerney, R. S. R. Candappa and K. Kanagasabapathy. A reviewer commented: “Of the younger members, R.D.Gabriel (with his desire for simplification), Ivan M. Fernando. George Claessen show progress. R. S. R. Kandappa’s [spelt with a K throughout the literature of the time], sole exhibit (Manjusri Thero)” – he, in fact, had two – “is a delightful and spontaneous work. One would like to see more of this artist. K. Kanagasabapathy fails. Walter Witharne is fast improving from ‘pretty’ paintings … The four bits of sculpture by the two new entrants are a notable contribution. Guerney’s excellence with the piece, Torso, and Blacker’s Elisa, The Litter, and Roslyn, are some of the best seen for a long time.”

Jayanta Padmanabha, sometime editor of the Ceylon Daily News, after a formal appraisal of the work on show, observed that following its custom, the Group had embellished their catalogues with “a number of dicta by an eminent artist – this time, Picasso. I cannot but feel,” wrote Padmanabha, “that those who have here followed that great man’s splendid but eccentric lead have paid too much attention to the injunction to ‘look for no explanation’ and too little on the axiom that ‘the artist always works out of necessity.’ But the ‘43 Group still supplies an important need by providing a centre for the artistic activities of present-day Ceylon, of whatever tendency or whatever degree of excellence. This year’s exhibition deserves to be supported especially not solely for its intrinsic merits but because the takings are to be given to the Lionel Wendt Memorial Fund.”

Some years later, Padmanabha had this advice to offer drawing upon an article on child art appearing in that month’s Marg, Mulk Raj Anand’s art magazine. The article, he said, had been “illustrated with paintings by children of very tender years, some of them … in the way of children’s paintings quite remarkable in quality. From the art of such babes and sucklings the ‘43 Group might learn if it could cultivate the necessary humility, that innocence of vision and integrity of feeling without which all art, however accomplished technically, ceased to be ‘a human activity’.”

Of this same exhibition, R. B. Tammita wrote in The Times of Ceylon: “It is not the sort of show you can take in at one glance or several glances. It has too many moods to it, and ‘tarry’ is my advice, if you want to catch the spirit of at least some of the many good pictures … Versatility is the keynote of this show, and from each of the artists you can pick out a picture or two you would like to keep.”

A columnist on the Observer had great fun at the expense of the art critics who had failed t o mention Gordon Davey in their reviews, but whose work had caught the eye of Lord Soulbury and the constitutional reforms commissioners then in Colombo. “Bleating ecstatically about the lyric metaphysical overtones and whatnot of the more unintelligible canvases, they managed to leave out of their reviews any mention of the beautiful water colours of Gordon (Brother) Davey, the only Service member of the ‘43 Group.” Lord Soulbury and his colleagues, it was reported, “were rather disappointed to hear that the gifted artist was an Englishman and not a Ceylonese.”

The Lionel Wendt Collection went up on view the following year. A newspaper report described it as a significant art show. It said: “The ‘43 Group has added another achievement to its list of successes in the exhibition of the Wendt Collection of paintings and drawings at 18 Guildford Crescent, Colombo.

‘The exhibition is a splendid one assessed even at facevalue: but it has an added interest in that it traces the development of two of Ceylon’s finest artists. Here, assembled under one roof, are works covering a large number of crucial years of George Keyt and to a lesser extent, Geoffrey Beling. Keyt is revealed as an especially interesting phenomenon, and there is an astonishing contrast between his early tentative and imitative representations and his more recent abstractions.

“There are also scores of fascinating canvases by Winzer, Ivan Peries, Manjusri Thero, Justin Daraniyagala, Wadsworth, Collette, George Claessen, Hugh Modder, Otto Scheinhammer, Gordon Davey, Alan Browne, and R. D. Gabriel.

SURAMBA DRUMMING. Photograph by Lionel Wendt

“The exhibition marks the beginning of a new era for 18 Guildford Crescent, the home of the late Mr Lionel Wendt … Exhibitions will be held here from time to time and the present collection of pictures will be the nucleus of a permanent collection that will do honour to Ceylon.”

In 1963, Harold Pieris, a life-trustee of the Lionel Wendt Memorial, decided to sell the collection because rats and rainwater in poorly secured storage under the stage of the auditorium threatened to destroy the lot. The collection consisted of 76 paintings, 21 prints and an original lithograph by Marie Laurencin. All the paintings needed extensive cleaning and some restoration before they were finally put up for auction. They made a formidable gallery that would indeed, have well served as the nucleus of a national collection. That Harry Pieris acquired the more important pieces is a measure of his singular good judgement.

With Lionel Wendt’s death, the mantle of responsibility for the ‘43 Group fell on Harry Pieris.