Harry Pieris (10 August 1904 - 14 March 1988)

Chapter VI

The Fragrance of Sapumal

Harry Pieris’ legacy

There used to be a small but cosy lounge looking out onto a cool garden in which numerous lemon trees grew, in Barnes Place, Colombo, that was, since the death of Lionel Wendt the setting for meetings of the ‘43 Group. On the main wall was an Ivon Hitchens landscape with, on either side, two dark but richly painted groups of brooding figures, like the witches in Macbeth by the Rumanian painter Madame Luiba Popesco. On another wall was a small and delightful Nayika by George Keyt; a portrait head on another. Some clay toy animals from Kelaniya stood on top of a bookcase. Beyond that lounge could be seen an easel with a portrait being worked on on it and more and more paintings, landscapes, compositions of all kinds, in oils, pastels, water colour. Among them was a small original Boudin – Scene at Havre; a temple mural copied by Manjusri – and work by members of the Group. The fragrance of the blossoms in the garden blended insinuatingly with the smell of linseed oil and turpentine (or was it petrol? Ivan Peries had grave doubts). This was the home of Harry Pieris.

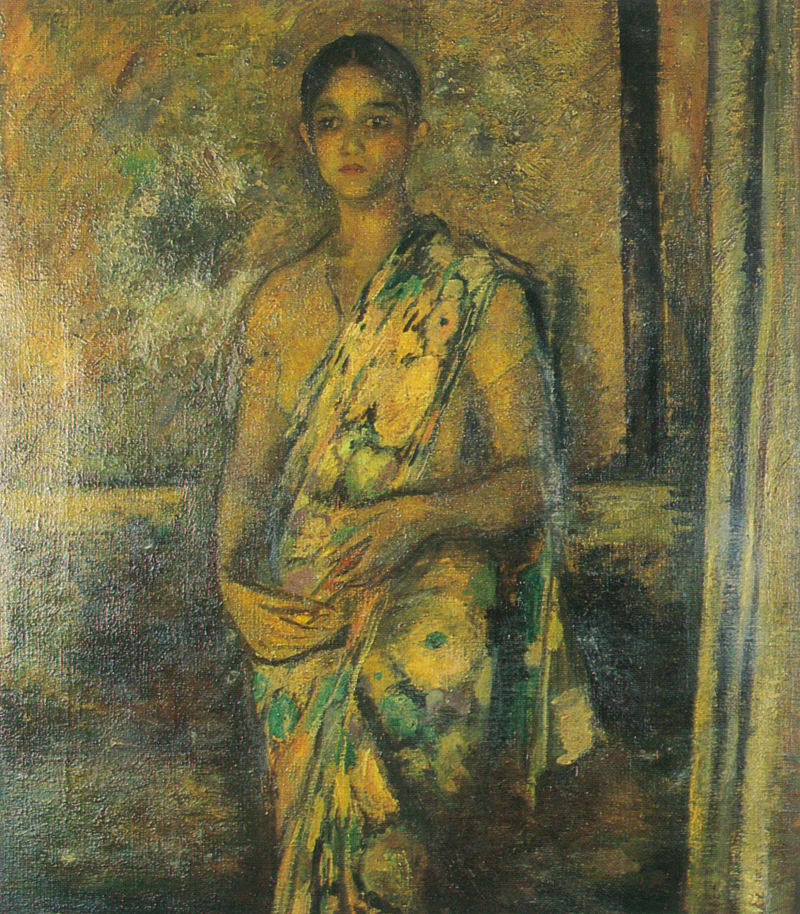

HARRY PIERIS: Indrani. Oil on canvas (42.5cm x 77 cm) Sapumal Foundation. Colombo

The meetings of the ‘43 Group, quite a few of which I had the special pleasure of attending, took place of an evening. Faithful to most such occasions was Justin Daraniyagala, but unfailing were Geoff Beling, Richard Gabriel. Aubrey Collette, and Gamini Warnasuriya. (Ivan Peries had already gone to live in London; so had George Claessen, via Melbourne). George Keyt did not attend in the years during which I sat as a member of the committee from 1954 to 1960. I do not recall a specific or formal agenda, but in the course of the evening any such matter as needed to be discussed quite obviously was discussed, and the conversation moved on to other equally enthralling topics. The art of northern Africa became the subject when it was suggested that the Group invite the young Arab artist. Ahmed ben Driss el Yakoubi, then in Sri Lanka with the American novelist Paul Bowles, to exhibit. Yakoubi’s abstract work led to the tossing around of observations on Miro or Paul Klee; then to Gamini Warnasuriya who was at that time himself creating fascinating compositions of a highly decorative nature. Most excitedly vocal on these occasions was Justin Daraniyagala who seemed perennially preoccupied with The Spaniard (Picasso). Daraniyagala was quite quixotic, tilting freely at everything before him. He had a lively mind, and in demolishing The Spaniard “off the walls”, he would draw upon a vast knowledge of the sources of the artist – African wood carving, for instance; his own collection of Sinhalese masks; the Musee de !’Homme in Paris; anthropology and Bronislaw Malinowski; the exhibition of drawings he had at the Leicester Gallery in London; and so forth. It was all supremely entertaining. They were always stimulating evenings, and Harry Pieris would remain the quintessential teacher drawing from the company their diverse contributions to the conversation. I first met Harry Pieris on a visit to him in the company of Ivan Peries. I had that year, 1950, become apprenticed to Ivan Peries, and that involved my escorting or driving him to meet friends and keep appointments nearly every day of the week. In his memoir for the present narrative. Ivan Peries described Harry Pieris as one of the greatest teachers he had known and the most brilliant of painters. I have sat many hours at a time listening to Harry Pieris, as indeed did Ivan Peries. It always amazed me that whatever his own programme for the day might have been, Harry Pieris had time for us, except, I suspect, for an hour or so after lunch when he retired for a siesta. It was on one of our casual, unannounced visits that Harry Pieris produced, from under the white divan that occupied most of that comfortable lounge, a portfolio of Rouault prints of the most exquisite quality, and another of Cezanne drawings made by a company of the name of Hanfstaengel, renowned for the meticulous accuracy of its reproductions. And then there grew, unwittingly and unobtrusively, an instruction in Cezanne’s cubist orientation, and the colour that Rouault took from stained glass.

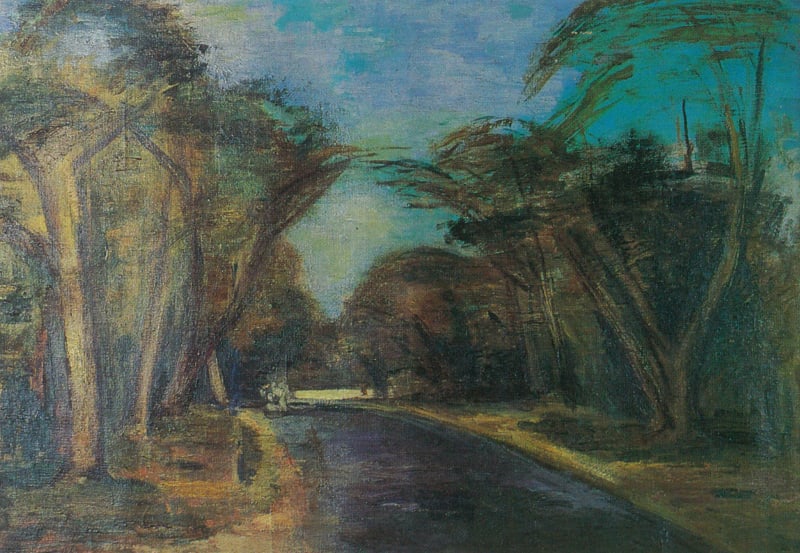

HARRY PIERIS: Buller’s Road, Colombo. Oil on canvas (72.5cm x 53cm) Sapumal Foundation, Colombo

Professor S. B. Dissanayake recognised the particular aura that lingered about Harry Pieris’ place in his fine essay to mark the artist’s 85th birthday, in the Daily News of I 6 August 1988. He was able to name jasmines, atteriyas and brunfelsias as adding their scent to the lemons in the garden. “His garden, house, the paintings in his house register his whole experience of life. He has, as it were, formulated that experience in entirely visual terms for everyone to see.”

Harry Pieris, born in 1904, studied painting first under Mudaliyar A. C. G. S. Amarasekera who, having exhausted himself, urged his parents to send the young painter to England. Pieris was 19 years of age when he entered the Royal College of Art in South Kensington. Sir William Rothenstein was principal, and it was he who first recognised Harry Pieris’ talent for portraiture. Rothenstein had written of Pieris at that time, in 1927: “During his first year he found himself in an unaccustomed atmosphere and had a good deal of difficulty in carrying on his drawing at the level of most of the students, but recently he has made quite surprising progress and shows particular promise as a painter of portraits. He has a marked gift in giving the essentials of the sitters’ characters, and his execution is most capable.” Pieris won the prize for the best portrait in 1926, for his portrait of his uncle, Sir James Pieris.

HARRY PIERIS: The Flowered Saree. Oil on canvas (50.5cm x 64cm) Sapumal Foundation, Colombo

Ivan Peries believed that it was Rothenstein who persuaded Harry Pieris to go on to Paris, which he did after a short stay in Colombo between 1927 and 1929. He lived six years there working under Robert Falk. It was in that time that he came to know and admire Madame Popesco. It was here, too, that Harry Pieris became acquainted with the Matisse family, had the privilege of Matisse’s informal criticism and enjoyed the hospitality of his home. Some tentative pieces sculpted by Harry Peries were cast in the Matisse foundry.

In 1935, Harry Pieris went to Bengal to teach at Rabindranath Thgore’s school in Santiniketan. William Rothenstein introduced Pieris to Thgore as “an artist of quite unusual ability and resource … I do not think that if you want anyone to help you to serve as a link between Eastern and Western Art you could get a better man.” Pieris returned to Sri Lanka in 1938 having painted the Bengal landscape and discovering for himself the cave paintings of Ajanta. Ivan Peries took great delight in the colours Harry Pieris used, relishing their names: “He used the same earth colours that we see in those paintings (at Ajanta). His palette was a combination of Indian red, yellow ochre, terre-verte, lapis lazuli and cerulean blue.”

Ivan Peries wrote: “On his return (to Sri Lanka) he painted a series of portraits based on his Indian experience and palette. I remember best of all three pictures which formed a superb triptych: one of Mrs David Rockwood, another of Amabelle Gunasekera and one of Miss Ponnasamy, in alizarin crimson and raw umber splashed with gold hems. If there is one picture of Harry Pieris’ that I would like to possess it is the portrait of Mrs David Rockwood. He also painted a portrait of Sita Rockwood, using pinks and viridian green. It was an object lesson in how to paint a young girl, with an empathy rare in portrait painting. He was never in demand as a portrait painter as he made no concessions to his sitters.”

Professor Dissanayake found an architectural quality in his method of construction to be the common denominator of all of Harry Pieris’ portraits. “The figures are constructed, erected as it were, from the ground up. This is quite apparent in his threequarter length and half-length portraits. Harry’s landscapes also share this quality … In Harry’s drawings and sketches this predilection for an architectural approach to his subjects becomes most apparent. He seems to be most interested in the ways the various parts of the human figure fall into position when it occupies a given space and in the relationships between figures within small groups.”

At a drawing lesson Harry Pieris once told me that as a student in London he had been required to paint a composition of figures for which he had no reference – no models. He had chosen Christ on the road to Emmaus as his subject, and found it one of the most daunting tasks he had ever undertaken. He was quite apologetic about it but took the opportunity to demonstrate the extent to which the live subject could draw from the artist responses which would clearly not be there had he been left to his imagination alone.

COLLETTE: Harry Pieris. Gouache on paper. Sapumal Foundation, Colombo.

Martin Russell writing in The Colombo Times of Ceylon annual of 1953, said that Harry Pieris had, “to some extent, sacrificed his position as a painter for that of a teacher … If one day, a National Portrait Gallery comes into existence in Sri Lanka. Harry Pieris’ work will have the premier place in it for our generation. His soft, glowing colours and careful design, and his acute powers of observation, are among the most impressive facets of Ceylon painting.”

Ever the teacher. Harry Pieris was passionate in his appeal for the preservation of the national heritage and for a place for a permanent exhibition of the best contemporary art. In a talk on radio, he asked what had been done, since Independence. “to educate our people to learn from the past and to create for the future? We have a fine art academy, now a department of aesthetic studies in a university, but I never noticed there a single reproduction of any of the ancient masterpieces of either this country or of Asia to inspire the students. This applies, as well, to all our schools in Colombo and the provinces. I have not come across any books in Sinhala on the art treasures of Asia or Europe which would be of help to the local student.

“I was fortunate as a young man to study art abroad. It was in Europe that I became acquainted with the art of the East and learned to appreciate it, because the museums and art galleries displayed great works both of the East and the West, and students were given every encouragement and facilities to study them … In this country the local student has no such facilities but this is a defect which is in the hands of our people to correct.”

Harry Pieris made a vigorous plea for a national gallery to contain copies of temple paintings, for instance, which he observed, were like the illuminated manuscripts of Europe, “invaluable records of past manners and customs; and easel paintings, such as the work of Justin Daraniyagala and David Paynter which”, he argued, “if suitably housed and exhibited could be of immense value to our students as well as those interested in contemporary art.”

To which end Harry Pieris established the Sapumal Foundation. (See Appendix C). “Sapumal” was his childhood nickname, given by members of the Pieris family. The flower of the sapu, it seems, never blooms in full but opens only partially – a comment on Harry Pieris’ turn of mind. In giving the establishment his nickname he has had the last laugh. His entire estate has been bequeathed to the foundation in the pursuit of his own enthusiasms, leaving none to his family bar a niece.

Ever the teacher, as I say, he never let the opportunity to instruct pass. On a visit to him in 1985, he introduced me to two young visitors, art students, who had come for advice. He turned their questions towards me as well, so that, he said, they could draw me out on whatever experience I may have had to offer. His most illustrious pupils were Ivan Peries and Richard Gabriel, both of whom of course venerated him, and about whom more anon.