W. J. G. Beling (21 September 1907 - 9 March 1992)

Chapter VII

Missionary Zeal

Beling’s basic truths

Geoff Beling was zealous about two matters: his deep and abiding Christian faith, and his belief in art as a means of expressing every human experience, the one overtaking the other, as it happens, but both adhered to with a vigour that remained undiminished over the decades. In the end, however, Beling was to abandon painting altogether in favour of a missionary vocation, but his contribution is inextricable from the story of modern painting in Sri Lanka. He guided the development of art education in the country from the time that he took over from C. F. Winzer in 1932 having developed as an artist under the influence of that excellent teacher and draughtsman.

In the beginning, astonishingly enough, the work of Winzer’s proteges seemed indistinguishable from each other. Beling and George Keyt showed marked similarities in the design and composition of their pictures, in the densities of their colour and in the very choice of the colour: indeed, even in the selection of topics – still lifes and landscapes – both drawing their styles from the same sources and rearranging their images in the same, somewhat austere manner. They were obviously both contemplating the same scene. But that was just a brief beginning: they have since moved in two very dissimilar directions.

BELING: The Blue Curtains. Oil on canvas (54.5cm x 63.5cm) Private collection, Melbourne. (Photography by Amahl Weereratne)

Winzer was impressed with these young painters, and he wrote of them in the January 1931 issue of The Studio, the London art magazine, describing the two painters from Sri Lanka, Keyt and Beling as “pioneers … in a more vital form of painting than that based on Royal Academy standards of taste.” He said: “Beling’s landscapes are admirably constructed and his handling of the endless variety of greens seen in tropical nature is an achievement in itself. His figures are more angular than those of Keyt and their movements less varied. Both, however, in their efforts are at one to express volume and construction in their canvases – qualities in which modern art of Asia, particularly in India, is so deficient … The maturing of these two artistic individualities is of the greatest importance to the whole direction of art in Ceylon.”

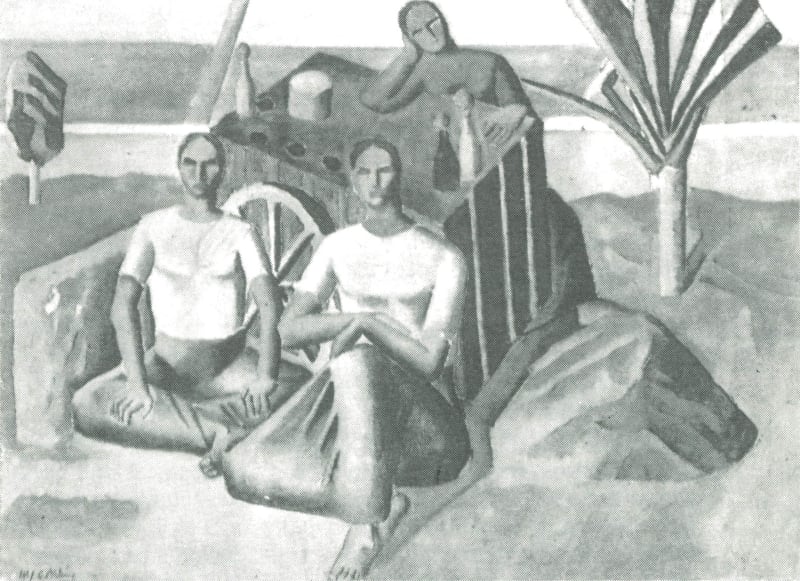

Armand Roulin, writing in The Times of Ceylon on Ceylon’s Renaissance, remarked that Beling’s pictures have “a tenderness and simplicity and fervour that proclaim the spiritual values he is now concerned about.” This was to be a recurrent feature of his work. It was a quality seen in different intensities in his chosen genres: still life, landscape, and portraiture. Perhaps the easiest to appreciate are the landscapes. They were arrangements of great masses, somewhat abstracted, but so constructed as to be almost geometric in their perfection. Each exercise presented a new problem, and each was resolved in the simplest manner. This became more complex when he took other elements with which to construct his pictures. The still life compositions are far more developed, and involved a bigger palette than Seling needed for his landscapes. But where he broke right out of this discipline was when he was confronted by a sitter whose portrait he was to paint. Then the personality of the subject gave rise to new emotions. The best example, one that has been seen widely by visitors to the arts centre, would be the Portrait of Lionel Wendt, draped in a flamboyant dressing-gown, seated at his Steinway Grand. Quite apart from the socio-historical detail the picture records – the dressing-gown, the grand piano, both extravagances of the leisured class – Seling displays a superb mastery of his craft. His painting is vigorous, the impasto free, fluent and effortless – a piece of the finest virtuosity. This kind of craftsmanship is rare; with Seling it was evidence of his enormous talents. Elsewhere, Beling’s compositions remained thoroughly formal, as may be observed in The Ice-cream Cart, or the group called Three Women.

BELING: Still Life. Oil on canvas (52cm x 49cm) Sapumal Foundation, Colombo

S. P. Amarasingham in the Sunday Times Illustrated found in Beling’s work a quality that was hard to define. “His lines and composition are classical and architectural, if one may so describe it. He succeeds in capturing a particular ‘atmosphere’ in such a way that it leaves an undying impression on one’s mind:’ It is tempting to suggest that the formality of these compositions derived from Beling’s early training in architecture. He was 19 when in 1926 he joined the Sir J. J. School of Art in Bombay to study architecture but where he also took art lessons. He had to abandon both courses and return to Sri Lanka upon his father’s death in 1928. W. W. Seling had been a very distinguished artist from whom Geoff Seling had had his first lessons. By the age of fifteen, Geoff Beling had acquired considerable skill and had frequently been winning prizes at the exhibitions of the Ceylon Society of Arts. In 1930 and 1932 he held joint exhibitions with George Keyt, and was greatly supported by Winzer, Wendt and Len van Geyzel.

But when in due course he himself ceased to practise the art of painting, Seling became tireless, as Chief Inspector of Art in the Education Department, in demonstrating what he believed were the absolute verities of the craft. He travelled widely within the Western province which was his region, talking to whole schools about the art of both East and West. He carried huge portfolios containing large prints of the masterpieces of Europe and of India. He encouraged Inspectors of Art in other parts of 57 the island to do likewise, so that between them they would be able to inculcate a greater appreciation of art in the children of the entire island. It was no mere chance, for instance, that brought S. R. Kanakasabai to exhibit at the first ‘43 Group exhibition. He was the Inspector of Art for the Northern province and had inevitably, fallen under the Beling spell. He brought fresh insights into the art of teaching children to draw and paint. Beling introduced an exercise in what was called free expression. This was a method which attempted to draw out from the child its own aesthetic, its own sense of beauty, its own appreciation of colour by releasing the child from the drudgery of such mechanical devices as perspective, etc. The role of the teacher was primarily to invite a child to respond to the immense pleasures of painting; then, as the child grew in awareness and self-knowledge, to guide it into the disciplines of the craft, but only after the child’s mind had been given wings on which to fly and soar and rise above the mundane.

BELING: The Ice-Cream Cart, 1924. Oil on canvas (45.5cm x 61cm) Sapumal Foundation. Colombo

There was a great deal in this that appealed to the missionary in Geoff Beling and but for a strange contradiction in his convictions would have provided the perfect text for a discussion on art and scholasticism. Though a deeply religious man, Beling did not believe that art should be used in the service of God. He would therefore not paint religious subjects and the greatest concession he ever made contrary to this principle was when he copied The Resurrection, a painting by El Greco whom he greatly admired.

He spoke and wrote a great deal on the subject of art education. In an article in the St Joseph’s College annual. 1949, he commented on the exhibitions of school art under Gabriel at St Joseph’s and Collette at Royal which he said “have been one of the aesthetic delights discerning people in Colombo have enjoyed year after year:’ Referring to the work at St Joseph’s, Beling said: “Though it ranges from the spontaneous and primitive efforts of young children to the more cultivated efforts of older students, one is always conscious of a discerning aesthetic influence controlling, guiding and inspiring the beautiful results obtained.”

It is also a measure of Geoff Beling’s great talent that he was invited to design the arts centre to commemorate his friend, Lionel Wendt. It was a project intended to gather under one roof resources for the pursuit of all the arts – a gallery, dark rooms and photographic studios, an auditorium and a modern, wellequipped stage.

In those days Beling travelled in an old Morris car which he had himself painted at different times. It was quite unorthodox in appearance but miraculous in performance as I have myself experienced. Mrs Cora Abraham once rented a part of the Beling home in Melbourne Avenue, Bambalapitiya, from where she launched, together with Sita Kulasekera (now Sita Gabriel), the art school which by an absentminded slip of Richard Gabriel’s pen took the name of the street and began to be called the Melbourne Art Classes for Children and Adults. I mention this here because the school was the product of Geoff Beling’s teaching, employed the methods he advocated and enjoyed his blessing. It was to produce many young and excellent artists some of whom were to enjoy association with the ‘43 Group.