George Claessen (5 May 1909 - 1 May 1999)

Chapter VIII

Draughtsman's Delight

The contemplative Claessen

In 1946 Ian Goonetileke edited for a new publishing house called Jataka a little book of drawings by George Claessen, who had been one of the founding members of the ‘43 Group. Arthur van Langenberg provided the Foreword in which he observed that “the appreciation of a drawing after the first sensation is past, creates a longing for serener, more lasting qualities which the artist is called upon to satisfy. The drawings of George Claessen possess these qualities.”

Tori de Sousa recognised this quality in Claessen’s work at the first exhibition of the Group. He described as moving and tender a large canvas called Mother and Child which had been accomplished “with a few telling strokes.” L. P. Goonetilleke, writing in the Daily News on the same exhibition, found this picture “striking for its effects achieved with remarkable economy.” He added that the “feeling for space and composition and unusual colour are noteworthy in his one portrait. The cumulative effect is memorable.” Another review of the time suggested that Claessen’s paintings (but not his drawings) were reminiscent of Rousseau. “There is a common element of childlike almost childish ingenuousness. Rousseau too, was self-taught. And Rousseau too (what a coincidence!) was a Customs’ man …” (though, in fact, he was a draughtsman in the Colombo Port Commission). Yet another critic, commenting on the fifth exhibition of the Group at Guildford Crescent, discovered that Claessen had “the uncanny gift of being able to invest the apparently trivial with a great deal of significance …”

CLAESSEN: Church by the Sea. Oil on canvas (38.5cm x 28.5) Michael & Fleur Mack Collection, Colombo

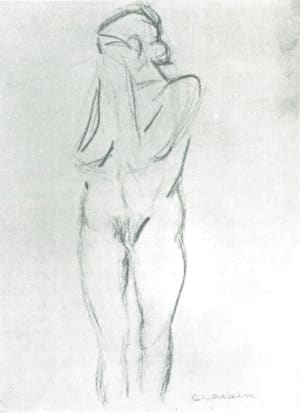

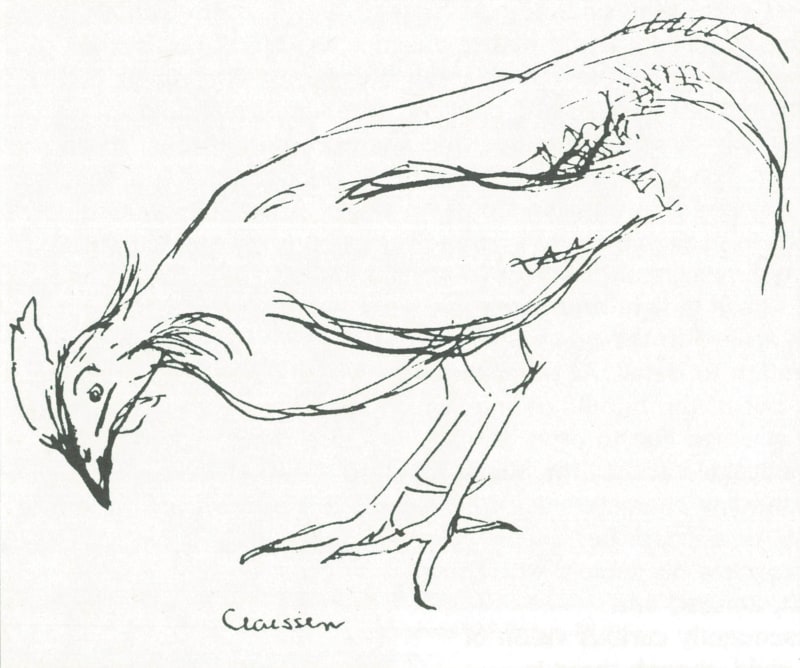

Ian Goonetileke established a new window into our little world of art with the publication of the book of twenty of Claessen’s drawings. Justin Daraniyagala wrote a masterly discourse on the art of drawing in the Ceylon Daily News in his review of the publication. All of it contributes greatly to an appreciation of the art of drawing but I cannot reproduce all of it here. The following, however, is salient: “There are two drawings in this collection – Sambur, and Chameleon – clearly inspired by Chinese brush drawing and another – Conjurer – by Japanese woodcuts, via Matisse. These influences, however, are well assimilated to become part of his personal idiom. The remaining drawings all show a subtle and resourceful use of the blurred outline, reinforced by modelling typical of European draughtsmanship. In obtaining the blurred edge Claessen makes use of more than one method. Like several painters with a lifelong devotion to the plastic qualities of objects he appears to avoid where possible, the clear-cut definition of the single outline so characteristic of Asiatic drawing. The initial statement, tentatively made, is modified and altered by other lines which overlap, cross, or run parallel to the original contour, but which in the finished drawings function as a single rather thick outline which in itself suffices to give the enclosed form considerable three-dimensional plasticity. In several instances this blurry line loses itself in light and extremely sensitive modelling carried out with an eye to the general shape of the form drawn, with little attention to detail. At other times he would stress, by darkening, one out of the bundle of lines which form this contour, and relate this stressed line to other similar lines elsewhere.” Later. Daraniyagala adds: “His humility before the model is an outstanding characteristic of his work. Be it a tree trunk, a female torso, or a lizard, he approaches his subject with the fresh, amazed and consequently curious vision of the child, though there is nothing childish about the way in which he registers his peculiar personal emotions and reactions.”

CLAESSEN: Nude. Black conte (23cm x 30.5cm)

Aubrey Collette had intimate knowledge of the vicissitudes the aspiring artist faced in those days. He had this tale to tell in the course of a discussion in the Times of Ceylon of the book of drawings: “When Claessen first painted the only means of exhibiting was through the Ceylon Society of Arts at the Art Gallery. This body had, from time immemorial, conducted competitive exhibitions in what was once described by a senior member as a ‘sporting spirit.’ Of recent times the sport took the form of a tug-of-war between the Atelier School (Mudaliyar Amarasekera) and the Government Technical College (l. D. A. Perera) – the result depending upon which was called upon to judge, the instructor of the Atelier, or the instructor of the Technical College. It was fortunate, therefore, that on a rare occasion the Society decided to have an experienced painter. Mr Harry Pieris, on its selection committee, which had hitherto consisted almost entirely of politicians and conjurors. Thus, for the first time, Claessen’s pictures passed the rejecters and were publicly exhibited … Claessen was by no means the first painter to suffer at the hands of the Philistines: George Keyt, Justin Daraniyagala and Geoff Beling had in the past been obscured by one or other of the phoneys favoured by a public whose taste had been corrupted from infancy.” That last aside carries much significance in the context of this story of the life and times of the ‘43 Group.

CLAESSEN: Jungle Cock. Pen and ink

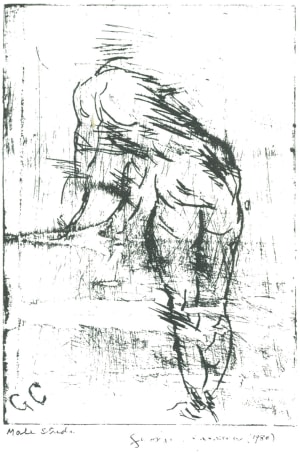

George Claessen’s work came to public notice at the regular exhibitions of the Group. They consisted largely of these small drawings – in pen and ink, in pencil, in charcoal – of seemingly mundane things seen and understood with genuine feeling. They were the result of quiet contemplation. They ceased to be trivial. They acquired a new life and became tangible, important and thoroughly real. These and the paintings were a statement of essentials – objects or people or animals stripped naked so as to reveal their essence alone.

CLAESSEN: Mother and Child. 1943. Oil on jute (84cm x 112cm) Mr & Mrs H. A. I. Goonetileke Collection, Oruwela

However, Sita Jayawardena in her review of the sixth exhibition of the Group in the Sunday Observer of 8 February 1948, though she thought Claessen’s Toys “excellent”, found his other exhibits not at his best. A similar observation was made of his work at the exhibition the previous year, a reviewer saying that Claessen was “becoming a disappointment. He can paint as I well remember from a first introduction to his work – a small blue-grey painting of surgeons round an operating table, and this has always made me hope for more.”

The Times Sunday Illustrated, in its series on painters by S. P. Amarasingham, said: “His drawings may be simple and even sketchy, but there is a great deal of feeling in every one of them. There is so much sincerity in his work that only the most insensitive will fail to respond emotionally to his pictures. Many of them speak aloud, tell a story. His picture, Toys, for instance, consists of just a doll, a playing card and some other oddment, but in any exhibition it compels attention. He uses a few and wellchosen colours with great effect and they lend a peculiar charm and quality to his work.”

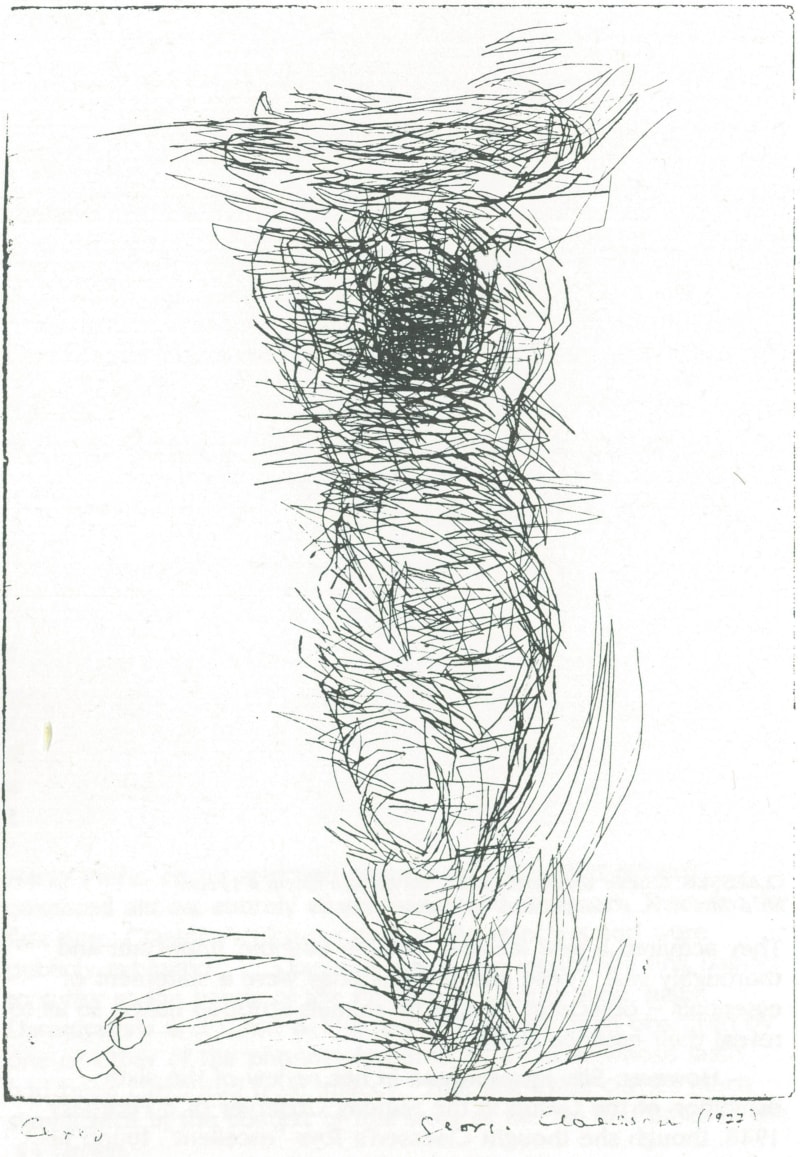

CLAESSEN: Ceres. 1977. Drypoint (17.8cm x 25.5cm)

In the late 1940s Claessen moved to Melbourne partly at least, it has been suggested because he had not received the recognition due to him as an artist in Sri Lanka. “Claessen has had more than his fair share of indifference to his art, even from those who claim to know art;’ the Sunday Times said. It was in Melbourne that he began to experiment with abstractions which were seen at a one-man show at the Velasquez Gallery there in 1948. He was to leave Melbourne in 1949 and to seek domicile in London where he now lives and works. He had several pictures at the Group’s first exhibition at the Imperial Institute and was among six ‘43 Group painters who exhibited in the Artists International Association Gallery in 1954. Stephen Bone liked his work. In the Manchester Guardian review of 15 January 1954. Bone referred to Claessen as the painter “of a large, dim, mural painting of card players, and as a draughtsman who has produced a number of excellent drawings.” Bone also drew attention to two abstract paintings belonging to the “soft” or “quasi-impressionist” school. John Berger observed “the nervous, good drawing of George Claessen” at the previous London exhibition at the Imperial Institute. Maurice Collis remarked that Claessen’s Mother and Child, an impressive painting on gunny-bag canvas and unframed, was “a monumental work of strong feeling.” William Graham, in The Studio considered that the figure and animal drawings alone put Claessen “in the front rank of any group of artists.”

CLAESSEN: Male Study, 1980. Drypoint (17.5cm x 25.5cm)

Claessen participated in the Venice Biennale of 1956 and at the fifth biennale held at the Meseu de Arte Moderna in 1959 in Sao Paulo. Brazil, where he won an award. He held a one-man exhibition at the New Vision Centre Gallery, London, in 1962 where he earned rich applause. Conroy Maddox writing in the 16-30 June issue of Arts Review said that Claessen’s “abstract expressionist approach … bears on Monet’s last period at Giverny (and) are plastic blossomings of a rocket-like launching in free space of the brush itelf. Beautifully toned colours are applied in distinct areas, with each colour tending to sound one note in a total chord of repeated, contrasting or complementary colours. The result is a surface that becomes a unity, a vibrant and dramatic unity, yet remains infinitely varied …” G. M. Butcher said there was “nothing accidental in the evolution of Claessen’s luminous mists; and there is very little that is either environmentally or specifically emotional. They are, instead, quintessentially calm, deliberate, contemplative.”

If this is true of Claessen’s abstract paintings it certainly confirms a basic truth about the artist seen from the beginning of his career – his sensitivity at all times. How true, indeed, of the drawings and the early oils which are, of course, more readily associated with his experience as an original Sri Lankan painter.